“When will we wake up and remember that divisiveness is not a sign of Christianity?”

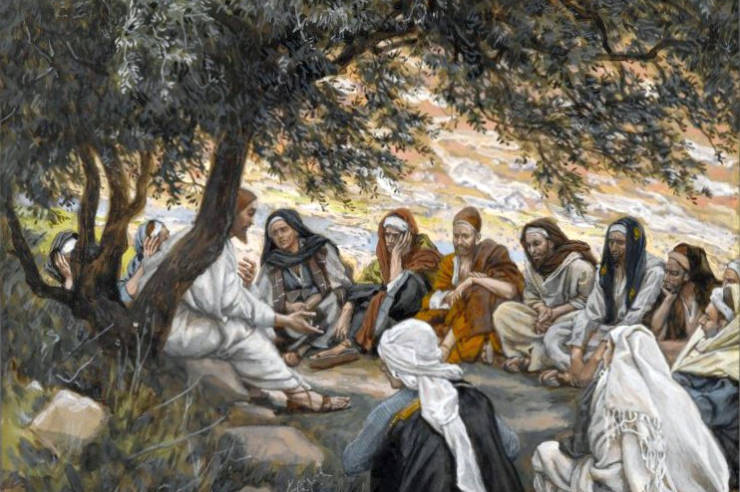

Image: “The Exhortation to the Apostles” by James Tissot [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Just before he died, Jesus told us how we would recognize his followers: “By this all men will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another” (John 13:35). It was true enough by the end of the second century, when Tertullian wrote about the witness of the Christians: “See how they love another!”

I hope someone would say the same today about us. But would they?

In this Sunday’s Gospel, Jesus warns us against divisiveness. The Apostles get anxious – maybe a bit perturbed? – that someone who isn’t one of their number is driving out demons in Jesus’ name. But Jesus assures them, “Do not prevent him. There is no one who performs a mighty deed in my name who can at the same time speak ill of me. For whoever is not against us is for us” (Mark 9:39-40).

I fear that one of the greatest arguments today against Christianity is our lack of love towards each other. This is not to say that Christians cannot disagree. In fact, because of the disunity in the Christian Church (a scandal and heartbreak), we must disagree. But we are still called to love.

Even beyond the disunity in the Christian Church, however, the animosity and bitterness towards fellow Catholics seems to abound these days. I was off of social media for two weeks while on pilgrimage in Rome, and the respite did me well. Coming back to the world of Twitter and Facebook, I was once again scandalized by how we treat each other.

We have forgotten how to love and we have forgotten how to dialogue. We have gotten very good at shouting and very bad at listening. What would be different if we had to speak the hurtful words we typed? Would we speak differently if we looked at eyes rather than screens?

I hope so.

I love the opportunities that social media has brought us. It has given me insights, connections, and even friends. But I often find myself wondering if it’s worth it all.

It’s a place where it’s easier to call people names than bear wrongs patiently. Calumny and libel flow easily. Judgments are rushed to a decision before anyone has time to explain or ask questions. We sit in our little thrones of self-righteousness, deciding what people meant by that post or tweet and judging them accordingly. People are profiles and handles instead of souls and bodies.

Even beyond social media, however, today we often find communities and parishes divided into factions and groups. Gossip and seeds of division are sown based on how you pray, whether you’re vaccinated, or what you think of this priest or this bishop or this Pope. When will we wake up and remember that divisiveness is not a sign of Christianity? By this all men will know that you are my disciples…

Friendships like the one shared between G. K. Chesterton and George Bernard Shaw are markedly absent in today’s climate. The two men disagreed about politics, religion, and pretty much everything under the sun. But after their fiery debates, they shared dinner together. Why? Not because they didn’t believe what they said on the debate stage. Not because they didn’t think the other person was wrong. But because they were friends.

They didn’t approve of each other’s views and they didn’t mince words to show this. But they also recognized the goodness in each other. “Mr. Shaw is a living in a comparatively Pagan world,” Chesterton once said. “He is something of a pagan himself and like many other pagans, he is a very fine man.” They respected each other. Indeed, they loved each other. Friendship and love do not mean condoning faults and ignoring sins, but to see each other as men made in the image and likeness of God.

We have lost the ability to talk to people as if they were people and not ideologies. We want to put everyone in nice tidy boxes with labels and assumptions. As a result, we have not only lost our ability to understand the other, we have lost our ability to love them.

People like to point out that Jesus ate with tax collectors and sinners, and it’s usually in a context where they want to try to tell themselves that Jesus didn’t care about sin or morality (ignoring his constant call to repentance and to “go and sin no more”). We can’t forget that He also ate with the scribes and the Pharisees. Rather than putting people in boxes marked “liberal” and “conservative” and rejecting one or the other (or both), he sought people out as people made in His image, and He loved them. This love meant calling them out when he saw them sinning, unafraid to make judgments on their actions, and always calling them to leave their sin behind and come to friendship with Him. But sometimes it also simply meant sharing a meal with them.

I don’t know how we will ever convert the world if we’re not willing to eat with them. And I don’t know how we’ll ever convert the world if we can’t stop fighting amongst ourselves.

Please share this article on Facebook and other social media below.

Please help us continue our mission!

We welcome both one-time and monthly donations. A monthly subscriber giving just $10 a month will help cover the cost of operating Integrated Catholic Life for one day! Please help us bring enriching and inspiring Catholic content to readers around the world by giving today.

Thank you and may God Bless you for supporting the work of Integrated Catholic Life! Integrated Catholic Life Inc is a nonprofit public charity under Internal Revenue Code Section 501(c)(3). These contributions are tax-deductible as provided under U.S. tax laws.