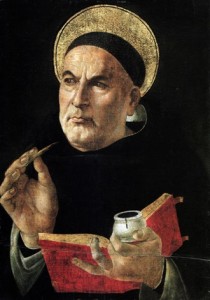

St. Thomas Aquinas by Botticelli

Karl Marx could not have missed the mark by a wider margin than when he said, “It is easy to become a saint if one does not want to become a man.” Apart from the fact that it is decidedly not easy to become a saint, is Marx’s failure to recognize that sanctity is man’s crowning achievement precisely as a human being, or, in the words of St. Irenaeus, “The glory of God is man fully alive.”

The virtue of manliness, therefore, is a natural element in the development of the saint. We are drawing our attention here to manliness as a quality that represents the fullness of the male, as opposed to womanliness that is perfective of the female.

There are no wimps in the catalogue of male saints. Timidity, conformity, and credulity are not the marks of a holy person, male or female. An illuminating and instructive example of the coincidence of manliness and sanctity is in the person of St. Thomas Aquinas. We may look at the manliness of Aquinas from the standpoint of: 1) his pedigree; 2) his mentor; 3) his character; 4) his mission.

His Pedigree:

St. Thomas’ great uncle was the bearded terror, Barbarossa. His second cousin was the brutal Emperor Frederick II of Germany, the infamous “Wonder of the World”. His family was related to Emperor Henry VI and to the Kings of Aragon, Castile, and France, as well as to a good half of the ruling houses of Europe. His father rode in armour behind imperial banners and stormed the Benedictine monastery at Monte Casino because the Emperor regarded it as a fortress of his enemy, the Pope. At his birth, therefore, this seventh and last son born of Count Landulf and the Countess Theodora of Teano, inherited the solemn obligation to take his place in the world and bring added lustre to his family’s already glorious name. Yet, Aquinas proved not to be so malleable. Despite his illustrious pedigree, whose manliness was never questioned, Aquinas gave his own manliness a different direction.

His Mentor:

Aquinas left his homeland in 1245 when he was twenty years of age and journeyed to Paris where he studied under Albert of Böllstadt who, even in his own lifetime, was known as Albertus Magnus, or Albert the Great. Like his celebrated pupil, Albert’s decision to become a Dominican was strongly opposed by his family, who had hoped that their intellectual prodigy would pursue a more worldly vocation.

St. Albert traveled throughout Europe on foot as a penniless friar. The Continent aptly dubbed him, “the Bishop of the Boots”. The good saint was, according to one commentator, “indefatigable, of immense strength and vitality, and totally dedicated to his work”.

Albert was a man of great learning whose academic interests were broad and deep. His literary output was vast, ranging from theology to botany. He was, in his own manliness, the ideal mentor for his young student. In 1248, when Albert went to Cologne, Thomas, now 23 years of age, went with him, and there finished his studies.

His Character:

The distinguished scholar, Etienne Gilson, has remarked that Aquinas possessed two intellectual virtues to a high degree that are rarely found in the same person. There was intellectual modesty which disposed St. Thomas to be open and respectful to all other thinkers, from the Latin Averroists, to Jewish theologians, to pagan philosophers. This modesty also meant that he was happy to allow things to be entirely themselves. Thus, he stated that, “The human intellect is measured by things so that man’s thought is not true on its own account but is called true in virtue of its conformity with things.”

Aquinas’ modesty was combined with his intellectual audacity. By virtue of his modesty, he saw things as they are; by virtue of his audacity he had the strength of mind to hold fast to the truth he grasped. Some thinkers have a great deal of intellectual modesty though they buckle under the pressure of public or personal opposition. Others see things in a distorted way, but foolishly cling to their errors despite reasonable evidence brought to their attention about their untenability.

Aquinas was manly enough to remain faithful, despite strong opposition to what he knew, in all humility, was right. One interesting instance were Aquinas expressed his manliness occurred while he was teaching at the University of Paris. Angered by the way the Averoists were corrupting the youth there with their sly, sophistical teaching, he challenged them to put their doctrine in writing and defend it in the open before men and not hand it out in the classroom to boys who were not able to defend themselves.

His Mission:

Thomas’ pedigree, his mentor, and his character well prepared him for the colossal mission he was destined to undertake. There were many battles he had to fight, though he always fought them with calmness, fairness, and sobriety. His first battle was against his family’s insistence that the young Thomas abandon all interest in becoming a Dominican friar and take his place in the world that was reserved for him. He was held prisoner for more than a year in the family’s castle. He rejected, sometimes heroically, all enticements and, true to his resolve, joined the Order of Preachers.

At Paris, he battled Guillaume de Saint-Amour, who denied the right of friars to teach. There would be fiercer battles to come. The greatest was his victorious battle in harmonizing reason with faith, philosophy with theology, and contemplation with action. His copious writings fill thirty-four volumes of double-column print (in the Vivès edition).

The manliness of St. Thomas Aquinas is amply demonstrated by his series of dramatic and enduring victories for the God, Church, and humanity. In summing up the accomplishments of Aquinas, Pope Leo XIII, in his encyclical, Aeterni Patris, wrote: “Reason, borne on the wings of Thomas to its human height, can scarcely rise higher, while faith could scarcely expect more or stronger aids from reason than those she obtained from Thomas.”

Among all the syntheses Aquinas was able to achieve, perhaps the most ironic is that of his manliness with his celebrated appellation as the “Angelic Doctor”.

Aquinas Today:

Today’s greatest moral battle involves abortion, which is at the very epicentre of the struggle between the Culture of Life and the Culture of Death. Many people recognize the humanity of the unborn, but are unwilling to come to their defence. On the other hand, many who are willing to stand up for any number of causes, refuse to see abortion as anything more than a choice. Both the modesty and audacity personified by St. Thomas are critically needed today so that the humanity of the unborn can be both recognized and defended.

Is it at all surprising then, astonishing as the story is, reported in the Spanish daily, La Razon and in magazines and newspapers throughout Eastern Europe, that none other than St. Thomas Aquinas himself would appear in a dream to change the mind and heart of a leading abortionist?

Stojan Adasevic is a Serbian doctor who has performed, over a period of twenty-six years, an estimated 48,000 abortions, sometimes as many as thirty-five in a single day. According to Adasevic’s written testimony, he “dreamed about a beautiful field full of children and young people who were playing and laughing, from 4 to 24 years of age, but who ran away from him in fear.” At this point in the dream, a man dressed in a black and white habit stared at him in silence. This dream was repeated night after night, and caused Adasvic to wake up each night in a cold sweat. One night, he asked this strange man dressed in what Catholics would recognize as a Dominican habit, to identify himself. “My name is Thomas Aquinas,” came the cryptic response. Naturally, since Adasevic’s entire education was in communist schools, he had never heard of him. Moreover, the medical textbooks of the Communist regime maintained that abortion is merely the removal of a “blob of tissue”. Although ultrasound images of the fetus arrived in the 80s, they had not changed Adasevic’s mind about the reality of the unborn.

Then it was Thomas’s turn to ask a question of his own: “Why don’t you ask me who these children are?” Aquinas quickly answered his own query: “They are the ones you killed with your abortions.” Adasevic awoke in amazement and vowed not to perform any more abortions.

When Adasevic informed his hospital that he would no longer do abortions, reprisals came swiftly and were quite severe. The hospital cut his salary in half, fired his daughter from her post, and took steps to prevent his son from entering the university.

After years of pressure and frustration that brought him to the brink of despair, he had another dream in which St. Thomas appeared to him. “You are my good friend, keep going,” said the Angelic Doctor. And, indeed, Adasevic has kept going. In addition to studying the works of Aquinas and returning to the Orthodox faith of his childhood, he has become Serbia’s most important and effective pro-life leader. Among his accomplishments is getting Dr. Bernard Nathanson’s film, “The Silent Scream,” aired on Yugoslav television.

Manliness is not machismo. Nor is it ostentation or braggadocio. The recognition of the humanity of the unborn and a willingness to come to their defence is an excellent illustration of this important virtue, and one that St. Thomas Aquinas continues to exemplify.

We value your comments and encourage you to leave your thoughts below. Please share this article with others in your network. Thank you! – The Editors.