Where now the horse and the rider? where is the horn that was blowing?

Where is the helm and the hauberk and the bright hair flowing?

Where is the hand on the harp-string, and the red fire glowing?

Where is the spring and the harvest and the tall corn growing?

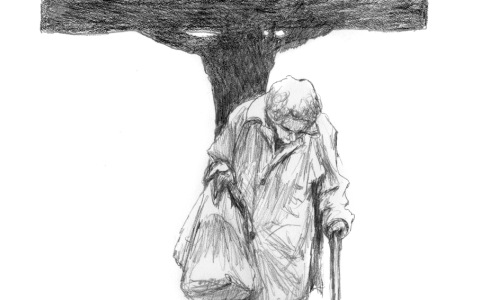

Eomer © by Jef Murray

These lines and more were chanted by Aragorn in The Lord of the Rings, and were attributed to a long lost poet of Rohan, the realm of the horse lords from J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth.

In my own imaginings, I’ve been roaming through Rohan in recent days. Like a keening heard across a great rolling plain, there is something about the Lenten season, coupled with the tales of Eorl the Young and his people, that pierces my heart. The Lenten desert begets reflection on the power, the pride, and the pain of the Rohirrim; for they, of all of Tolkien’s feigned tribes, are the most mortal. And it is their aching mortality that infects my musings.

Rohan is, of course, a sort of lens offered us with which to see our own world more clearly. When we look into this glass, we may believe we are seeing a sub-created realm of proud and ancient warriors, but in fact, we are descrying ourselves from an unusual vantage point. This is what G.K. Chesterton described in his tale from Orthodoxy, wherein he posits a traveler leaving England to seek distant shores. In that tale, and unbeknownst to the traveler himself, he lands once again in England, and is only thus able to see his own world afresh.

Rohan illustrates what it means to be caught without shelter in the storms of time, without refuge and without any certain hope in anything beyond our five senses. The people of Rohan were like the Greek Stoics, who had no faith in anything transcendental, but who nevertheless held to a high and noble code of right and wrong. And the warriors of Rohan tried to find a way for noble deeds alone to bring them a sort of fleeting immortality, a way of being remembered by future generations in tales and in song, even after life, and labor, and love had all lapsed away.

I suspect we all, at times, ponder what we will leave behind us on this Middle-earth once we are gone. When I paint the windswept plains of Rohan, I am reminded that most of the original seven wonders of the ancient world are no more…where they once stood is now as barren as the grasslands that surrounded Edoras, or as empty as the outskirts of Greytown in C.S. Lewis’ The Great Divorce. What became of all those who toiled to erect the Lighthouse of Alexandria? Or the Hanging Gardens of Babylon? Does anyone remember their names, or the stories they once shared? Was there any point to their efforts, now that even their greatest works are but rumors on a fickle wind?

And yet Theoden, the king of Rohan who came to the aid of a besieged Gondor, was not entirely without hope and faith. For, in his final words, he affirmed his belief that he could now rest in honor with his forefathers, since he had proven himself trustworthy and valiant in battle and in the great ongoing struggle against evil.

Rohan existed in a pre-Christian era: in a time when the final resting place of Elves was known by the Wise, but when the fate of men, once they perished, was yet a mystery. Eru Iluvatar had not disclosed His plans for mankind, not even to the Valar, during the long ages when the Rohirrim bred their steeds in the grassy plains of the Mark.

As a result, the days of King Theoden were like the dark time of Lent…a time of trouble, of doubt, and of turbulence. In such times we can, in our own age, take comfort in the coming of Eastertide; but for the Rohirrim, the coming of Christ was yet to be. Nothing in their lore assured them of what they might find once they crossed the threshold from life into death.

But they desperately desired that their deeds not be forgotten. They enjoyed the good things that they found on this earth: they raised their families; they defended the innocent; they fought against slavery and exploitation; they welcomed aid and wisdom where they found it. They knew not that one day a Savior would come, yet they lived each day desperately hoping that, when all ceased to be, there would yet be something remaining to mark their passage, something that the winds of time could not entirely erase. Surely all of the goodness of life could not just vanish with their final breath; surely there was something more than just this earthly realm…

C.S. Lewis once said “If we find ourselves with a desire that nothing in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that we were made for another world.”

I believe the witness of Rohan, and of all noble civilizations, is that we were made for another world. There is a reason why we seek after truth, goodness, and beauty, even when it appears that these will never entirely be within our grasp; and that reason, that yearning, does not cease when darkness falls. Nay, in truth, it is only then that we may come to know how grand and glorious a tale it is that we have been a part of all along.

I wish for you and yours a soul-nourishing Lenten season. I pray that these forty days might strengthen your love of what is good and noble, and that you might awaken on Easter morning to the certainty that all of the good that you do on this earth is not in vain, and that the darkness will never prevail.

Nai Eru lye mánata

Jef

Please help us in our mission to assist readers to integrate their Catholic faith, family and work. Share this article with your family and friends via email and social media. We value your comments and encourage you to leave your thoughts below. Thank you! – The Editors