His expectations may have seemed intense, but so was his mercy.

I remember hearing a powerful homily by Bishop Barron on the excessive demand of God and the extravagant mercy of God. We have a God who calls us to be a perfect, but also a God who welcomes back the prodigal son. Bishop Barron pointed out that we have a hard time holding these together.

“How do you balance his infinite mercy …. With his infinite demands? … It’s so difficult.. that we often make a choice. We turn it into a zero-sum game. In other words, the more you emphasize God’s mercy, the less you emphasize his demands. Or the more you emphasize God’s moral demands, the less you emphasize his mercy.” He points out, however, that this leads to two different but dangerous misunderstandings of God.

If we emphasize the demand without the mercy, we make God a tyrant. If we emphasize mercy without the demand, he becomes a God who is just there to indulge you, never calls you to spiritual greatness. Neither of these extremes are the biblical God.

When I think about the lessons of the life and pontificate of St. John Paul II. I am almost overwhelmed into writer’s block. Here is the Pope that made such a radical difference in my life and the life of so many of my friends and family members. I was living in Rome during his last months of life and was present at his funeral. I was in Rome for his very first feast day and was present at the very first feast day Mass celebrated at his tomb that morning.

My generation called itself the John Paul II Generation, because he was the one that called us to radical holiness. He was the one who spoke to us in Denver in 1993 and shook us out of our mediocrity. He called us to himself at World Youth Day after World Youth Day, telling us not to settle, to be courageous, and not to fear.

A week after he died, while being interviewed on television about the impact he had on young people, one of my friends summarized it best. “He knew what we were capable of, and he expected it.”

That is why the young people flocked to him. That is why we chanted his name. That is why he continually captivated us, even as he could barely look at us, hunched over in pain, carrying the cross of his failing body. In a world that handed us drugs and condoms, called us slackers and self-absorbed, and set the bar low, he did the opposite. He called us to seek holiness and to live radical lives of self-gift. He knew we were capable of it, and expected it. He made great demands.

But he also extended great mercy. Here was the Pope who wrote the words of Dives in misericordia, his stunning encyclical on mercy. He then lived out that encyclical in his own life, looking into the eyes of a man who tried to assassinate him and forgiving him, regardless of whether Ali Ağca was repentant.

After personally suffering so much in the face of evil, at the hands of sinners and some of the worst atrocities of the twentieth century, one might think that John Paul would preach the difficult message of justice. Instead, he preached mercy:

“Modern man often anxiously wonders about the solution to the terrible tensions which have built up in the world and which entangle humanity. And if at times he lacks the courage to utter the word ‘mercy,’ or if in his conscience empty of religious content he does not find the equivalent, so much greater is the need for the Church to utter his word, not only in her own name but also in the name of all the men and women of our time” (Dives in misericordia, 15).

John Paul II did not leave us to God’s justice, but to his mercy. He closed the second millennium and opened the third by asking forgiveness for the sins of the Church and extending the great gift of mercy.

St. John Paul II emphasized the great demands of the Gospel. He called us to holiness. He called us to radical witness in an increasingly secular world. He called us to repentance.

“In no passage of the Gospel message does forgiveness, or mercy as its source, mean indulgence towards evil, towards scandals, towards injury or insult. In any case, reparation for evil and scandal, compensation for injury, and satisfaction for insult are conditions for forgiveness” (Dives in misericordia, 14).

But he also extended mercy, opening wide the doors to the love of God. He repeatedly reminded us to not be afraid and to come back to the loving arms of the Father. His expectations may have seemed intense, but so was his mercy.

“Right from the beginning of my ministry in St. Peter’s See in Rome, I consider this message [of Divine Mercy] my special task. Providence has assigned it to me in the present situation of man, the Church and the world. It could be said that precisely this situation assigned that message to me as my task before God.”

Each year, the feast of John Paul II almost seems surreal to me. Here is a man that we knew, we saw, and with whom we prayed. And yet now we pray to him, we look to him, and ask him for help. What can he continue to teach us? Perhaps today, as society continues to divide, separate, alienate, or shame, he wants to teach us about the loving mercy of God.

The Optional Memorial of Saint John Paul II (1920-2005) is October 22.

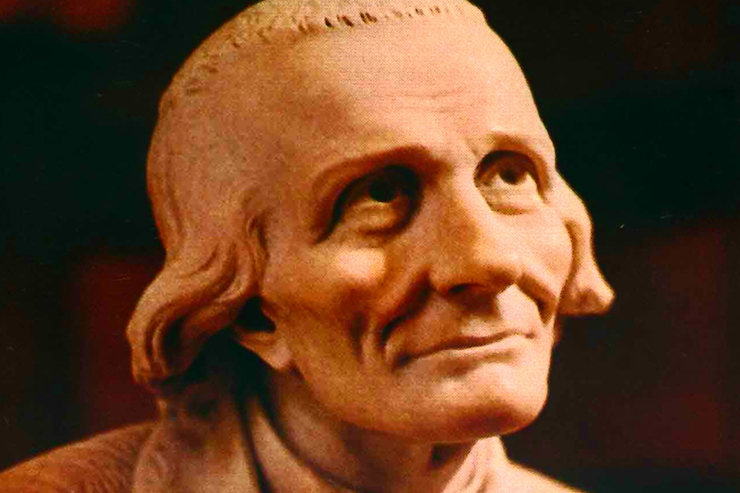

Image: Statue of Pope John Paul II at the St. Thomas Mount National Shrine in Chennai shot during the golden hour (shutterstock | By JoostP)