Sunday Reflection—The Pharisee and the Publican

by Marcellino D'Ambrosio, Ph.D. | October 26, 2019 9:00 am

[1]

[1]

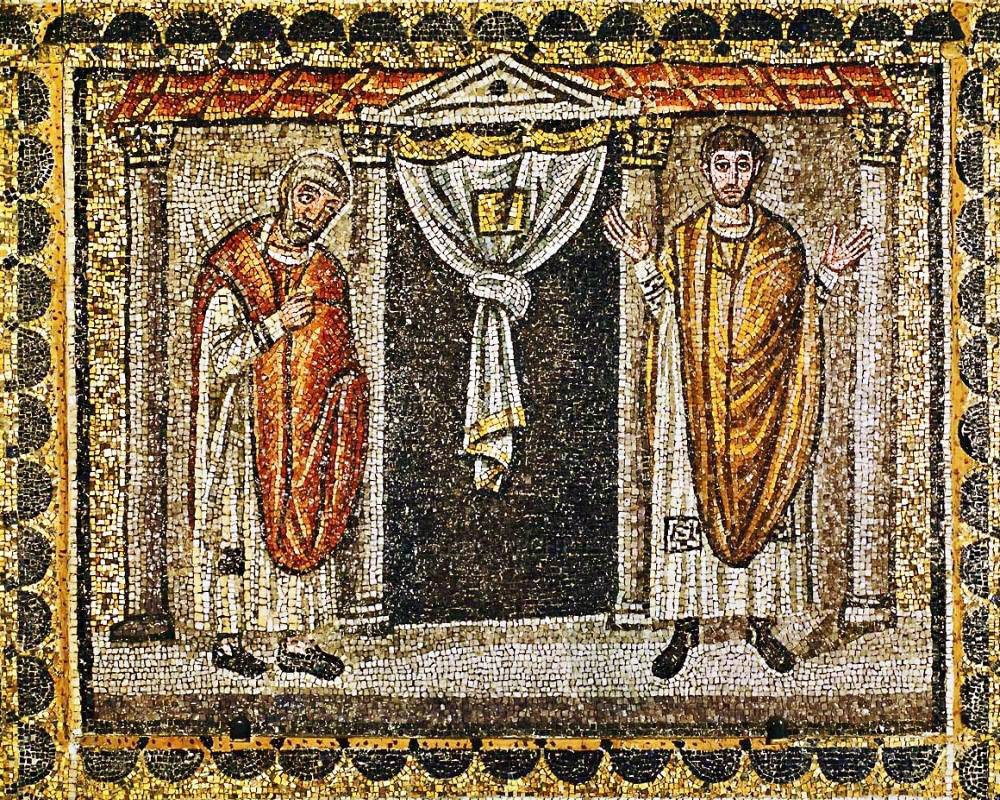

The parable of the Pharisee and the Publican (tax collector) in Luke 18 teaches us a lot about pride, humility and . . . insanity. It even gives us insight into one of the principal battle cries of the Protestant Reformation — “sola gratia” or “grace alone.”

The Mass readings for the Thirtieth Sunday in Ordinary Time (Year C) are Sirach 35:12-14, 16-18; Psalms 34:2-3, 17-18, 19, 23; Second Timothy 4:6-8, 16-18; Luke 18:9-14[2].

Each year, at one of our country’s leading Catholic universities, a professor does a survey with each incoming class of students. He puts to them this question: “If you were to die tonight and appear at the pearly gates, what would be your entry ticket?”

Nine out of ten bet their good character and behavior will gain them admission.

THE PHARISEE: PRIDE AS INSANITY

This is exactly the strategy used by the Pharisee in the parable told by Jesus in Luke 18:9-14.

As we listen to this story today, the Pharisee strikes us as conceited. His real problem, though, is that he, like the students noted above, is out of touch with reality. And, by the way, being out of touch with reality is the definition of insanity.

Reality is that we are creatures and God is the creator. Heaven is the experience of sharing intimately in God’s inner life, participating in his immortality and friendship. We have less of a claim to intimate friendship with God than a flea has to intimate friendship with us. As the Danish philosopher Kierkegaard said, there is an infinite qualitative distance between us and God.

JUSTICE & MERIT

In fact, standing on our own merits, we have absolutely no claim whatsoever on God. A claim is based on justice. Justice is about receiving our due and paying what we owe. We receive our very being and all we need to sustain that being from God. Therefore we owe him everything – perfect love, honor, obedience, and worship. Showing up at church from time to time, tossing a few bucks in the basket, and trying to be basically decent people doesn’t quite cover the debt.

In fact, considering what we all owe, the Pharisee’s merits don’t appear all that more impressive than the tax-collector’s.

[3]

[3]

That’s why God sent Jesus. Through his act of perfect humility, obedience and love on the cross, He paid the debt that the entire race owed to God. That’s justice. And then he credited it to our account. That’s mercy. Another name for mercy is grace.

IT’S ALL GRACE

In the sixteenth century, Martin Luther, an Augustinian friar, studied St. Paul’s letters and came to a startling conclusion: “for by grace you have been saved through faith; and this is not your own doing, it is the gift of God–not because of works, lest any man should boast” (Eph 2:8). Wait a minute. Isn’t this Protestant doctrine? No. In the words of Peter Kreeft, the Protestant Reformation began when a Catholic monk rediscovered a Catholic doctrine in a Catholic book.

Talking to most Catholics in Luther’s day, you’d never know this was Catholic doctrine. And the college survey noted above illustrates that the same is regrettably true today. Most appear to be under the illusion of the Pharisee that they deserve salvation based on their good deeds.

The Church’s teaching has always been that it’s all grace. Whatever natural blessings we enjoy–health, job, family, education–are gifts. Did we have to labor at all to attain what we have? Usually. But we were created out of nothing. Our very existence and ability to labor is a gift. If we enjoy a personal, intimate relationship with God as our Father and Jesus as our brother, that’s all gift as well.

Do we have to labor spiritually to do God’s will and walk in the path of good works that God has marked out for us? (Ephesians 2:10). Of course. But the very ability to know God’s will and love as God loves is pure grace.

THE PUBLICAN & MERCY

The publican was under no illusions: he knew that he deserved nothing but judgment. So he asked for mercy. This is the sane thing to do. The Pharisee, under the illusion that his works made him righteous, didn’t think he needed grace, so didn’t ask. That’s insane.

Humility is not only sane, it is liberating. It enables us to stop thinking about what we’ve done and what we deserve and focus instead on what He’s done and how much He deserves. Humility may begin with beating one’s breast and looking at the ground. After all, the term “humility” comes from the word “humus” or earth. But mature humility looks exuberantly up to heaven. Not with the arrogance of the Pharisee, mind you, but with joyful thanksgiving of those who are thrilled to know that they are loved.

[4]Please share on Facebook and other social media you choose below:

[4]Please share on Facebook and other social media you choose below:

- [Image]: http://www.integratedcatholiclife.org/wp-content/uploads/sunday-scripture-reflections-w740x493.jpg

- Sirach 35:12-14, 16-18; Psalms 34:2-3, 17-18, 19, 23; Second Timothy 4:6-8, 16-18; Luke 18:9-14: http://www.usccb.org/bible/readings/102719.cfm

- [Image]: https://www.crossroadsinitiative.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/parable-of-pharisee-and-the-tas-collector-basilica-di-santapollinare-nuovo-ravenna-italy-6th-century.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.integratedcatholiclife.org/donate/

Source URL: https://integratedcatholiclife.org/2019/10/dambrosio-sunday-reflection-pharisee-and-the-publican/