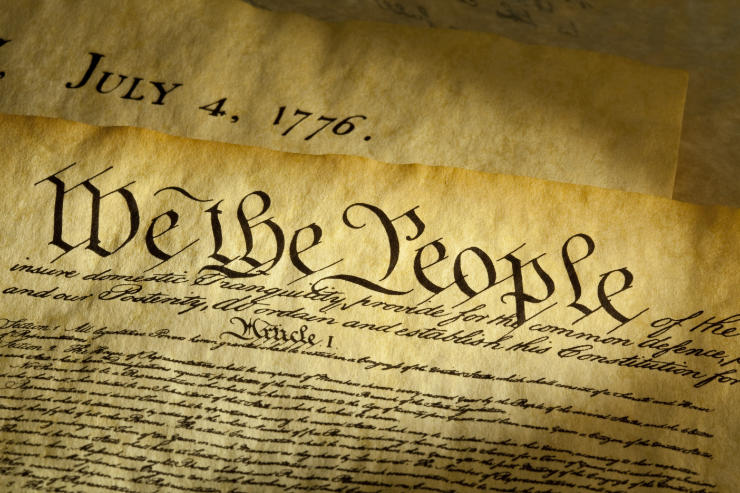

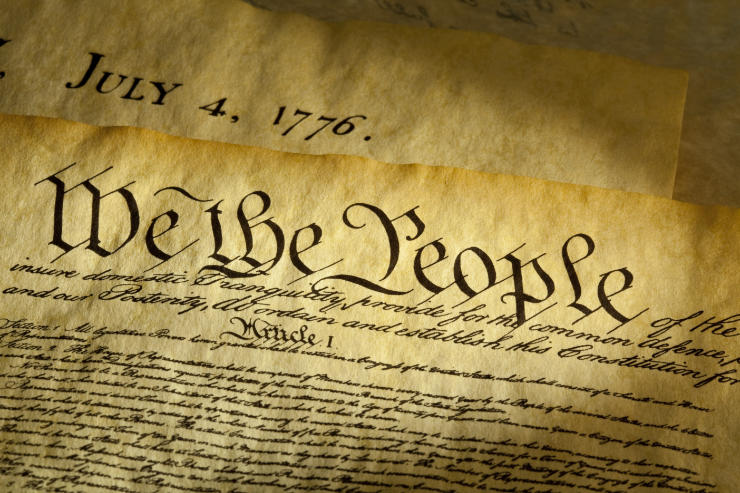

We the People are the opening words of the preamble to the Constitution of the USA. The document underneath is a copy of the Declaration of Independence with the date, July 4, 1776, showing.

I have been following George Will’s thought for a long time. I’m old enough to remember when his column occupied the last page of Newsweek magazine every other week and when he sat in the chair of conservative thought on David Brinkley’s Sunday morning political talk show. I have long admired his graceful literary style and his clipped, smart manner of speech. Will was always especially good when, with lawyerly precision, he would take apart the sloppy thinking of one of his intellectual or political opponents. When I taught an introductory course in political philosophy at Mundelein Seminary many years ago, I used Will’s book Statecraft as Soulcraft to get across to my students what the ancients meant by the moral purpose of government.

And so it was with great interest that I turned to Will’s latest offering, a massive volume called The Conservative Sensibility, a book that both in size and scope certainly qualifies as the author’s opus magnum. Will’s central argument is crucially important. The American experiment in democracy rests, he says, upon the epistemological conviction that there are political rights, grounded in a relatively stable human nature, that precede the actions and decisions of government. These rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness are not the gifts of the state; rather, the state exists to guarantee them, or to use the word that Will considers the most important in the entire prologue to the Declaration of Independence, to “secure” them. Thus is government properly and severely limited and tyranny kept, at least in principle, at bay. In accord with both Hobbes and Locke, Will holds that the purpose of the government finally is to provide an arena for the fullest possible expression of individual freedom. Much of the first half of The Conservative Sensibility consists of a vigorous critique of the “progressivism,” with its roots in Hegelian philosophy and the practical politics of Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, that would construe government’s purpose as the reshaping of a fundamentally plastic and malleable human nature. What this has led to, on Will’s reading, is today’s fussily intrusive nanny state, which claims the right to interfere with every nook and cranny of human endeavor.

With much of this I found myself in profound agreement. It is indeed a pivotal feature of Catholic social teaching that an objective human nature exists and that the rights associated with it are inherent and not artificial constructs of the culture or the state. Accordingly, it is certainly good that government’s tendency toward imperial expansion be constrained. But as George Will’s presentation unfolded, I found myself far less sympathetic with his vision. What becomes clear is that Will shares, with Hobbes and Locke and their disciple Thomas Jefferson, a morally minimalistic understanding of the arena of freedom that government exists to protect. All three of those modern political theorists denied that we can know with certitude the true nature of human happiness or the proper goal of the moral life—and hence they left the determination of those matters up to the individual. Jefferson expressed this famously as the right to pursue happiness as one sees fit. The government’s role, on this interpretation, is to assure the least conflict among the myriad individuals seeking their particular version of fulfillment. The only moral bedrock in this scenario is the life and freedom of each actor.

Catholic social teaching has long been suspicious of just this sort of morally minimalist individualism. Central to the Church’s thinking on politics is the conviction that ethical principles, available to the searching intellect of any person of good will, ought to govern the moves of individuals within the society, and moreover, that the nation as a whole ought to be informed by a clear sense of the common good—that is to say, some shared social value that goes beyond simply what individuals might seek for themselves. Pace Will, the government itself plays a role in the application of this moral framework precisely in the measure that law has both a protective and directive function. It both holds off threats to human flourishing and, since it is, to a degree, a teacher of what the society morally approves and disapproves, also actively guides the desires of citizens. But beyond this, mediating institutions—the family, social clubs, fraternal organizations, unions, and above all, religion—help to fill the public space with moral purpose. And in this way, freedom becomes so much more than simply “doing what we want.” It commences to function, as John Paul II put it, as “the right to do as we ought.” For the mainstream of Catholic political thought, the free market and the free public space are legitimate only in the measure that they are informed and circumscribed by this vibrant moral intuition. George Will quite rightly excoriates the neo-gnostic program of contemporary “progressivism,” but he oughtn’t to conflate that dysfunctional philosophy with a commitment to authentic freedom in the public square.

When we come to the end of The Conservative Sensibility, we see more clearly the reason for this thin interpretation of the political enterprise. George Will is an atheist, and he insists that, despite the religiously tinged language of some of the Founding Fathers, the American political project can function just fine without reference to God. The problem here is twofold. First, when God is denied, one must affirm some version of Hobbes’ metaphysics, for, in the absence of God, that which would draw things together ontologically, and eventually politically, has disappeared. Secondly, the negation of God means that objective ethical values have no real ground, and hence morality becomes, at the end of the day, a matter of clashing subjective convictions and passions. Catholic social teaching would argue that the rhetoric of the Founders regarding the relation between inalienable rights and the will of God is not pious boilerplate but indeed the very foundation of the democratic political project.

So perhaps one cheer for The Conservative Sensibility. Will gets some important things right, but he gets some even more basic things quite wrong.

Editor’s Note: Bishop Barron’s article appeared August 6, 2019 on the Word on Fire website and is presented here with the kind permission of the author.