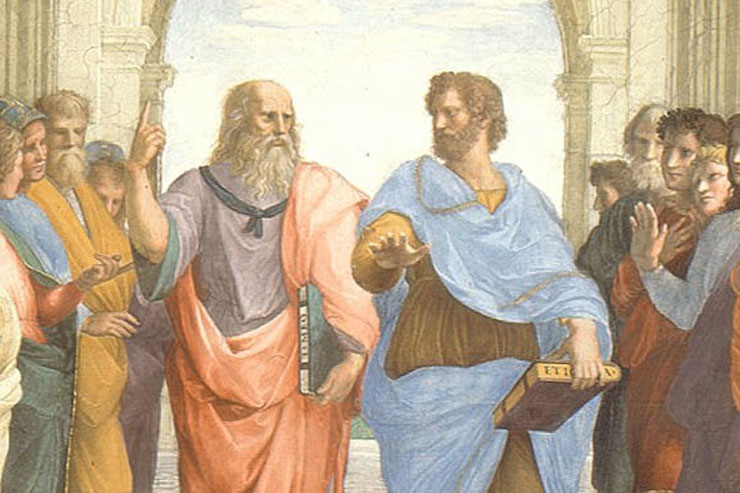

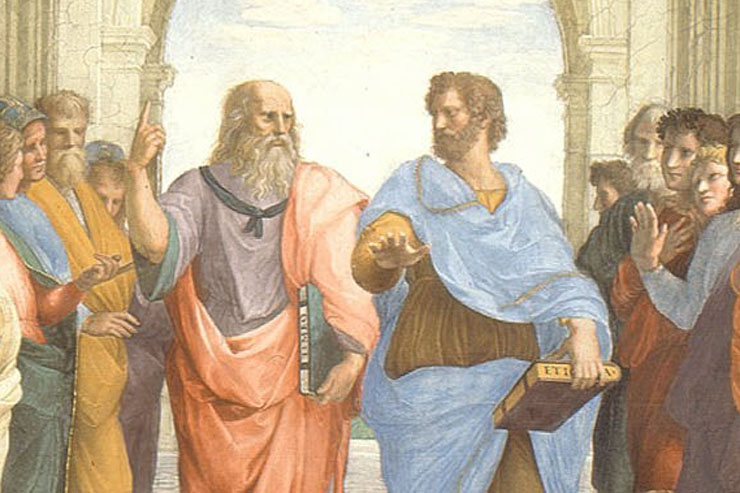

“The School of Athens” (detail showing Aristotle with the elder Plato) by Raphael

Ten years ago, when I was a visiting scholar at the North American College in Rome, I fell into a spirited conversation with one of the seminarians about the state of evangelization in America. We both were bemoaning the fact that the “new” atheists—Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and others—were regularly attacking religion, and I commented that no Christian spokesman had managed to engage the enemies of the faith well on the public scene. To this, my seminarian friend responded, “Yeah, but have you seen William Lane Craig?” I admitted I hadn’t. He told me that Craig, an evangelical Protestant, was by far the most effective spokesman for the Christian point of view and that he had taken on the atheists with great intelligence, wit, and panache. That night, I looked up Dr. Craig on YouTube and watched, with fascination, his debates with the superstars of the atheist movement. From that evening on I was a fan.

This is why, when I was invited by the good people at the Claremont Center for Reason, Religion, and Public Affairs to participate in an all-day dialogue with William Lane Craig, I jumped at the opportunity. The event took place last Saturday and involved an exchange of philosophical papers in the afternoon and a two-hour public conversation in the evening. The topic I chose for the philosophical discussion was the technical question of God’s simplicity, or the identity of essence and existence in God, a teaching of Thomas Aquinas that I strongly support and that Dr. Craig vehemently denies. We and the twenty-five or so other scholars around the table spent a good hour and a half digging into the weeds of this controversy. Dr. Craig chose to speak on a topic that he has been researching a great deal in recent years, namely, penal substitution, the idea that on the cross Jesus received the punishment for sin that we deserved and hence satisfied divine justice and freed us from our guilt. I agreed that this idea can be found both in the Bible and the theological tradition but that it should be combined with a number of other models of explanation, most notably the so-called Christus-Victor theory proposed by many of the Church Fathers. In regard to both issues, fault lines did indeed open up between the Catholics and the Protestants around the table, but I believe that a fair amount of common ground was also found, especially around the issue of penal substitution.

The evening session, which played out in front of an audience of about 1,200 in person and around 25,000 watching through live stream, was a structured conversation between Dr. Craig and me. We covered a slew of topics, but for the purposes of this article I would like to draw attention only to a few.

First, we both expressed, rather passionately, our opposition to dumbed-down versions of Christianity. One reason that so many young people are leaving Christianity is that religious teachers and leaders have presented such anemic, superficial, and intellectually uncompelling versions of the faith. Therefore the needful thing, we both affirmed, is a revival of classical Christian apologetics, that is to say, an intelligent defense of the faith against its rational critics.

We also spent a good deal of time talking about religion in relation to science, for the supposed conflict between these two disciplines is often given as the number one reason that people leave religion behind. Both Dr. Craig and I insisted that authentic faith ought never to be construed as below reason but only as beyond and inclusive of reason. In fact, Craig observed that science, rightly understood, can often provide premises for apologetic arguments, and I pointed out that a religious assumption, namely the intelligibility of the universe, is the condition for the possibility of science. We came together in our emphatic rejection of “scientism,” which is the reduction of all knowledge to the scientific form of knowledge, a position that is widely held among young people but that rests upon a fundamental inconsistency. For one could never determine, on scientific grounds, the principle that only scientific knowledge counts as authentic.

One of my favorite moments in the conversation was when we were invited to ask one another questions. Dr. Craig asked me why I think it is advisable to use beauty in the evangelical enterprise. I gave my answer, the details of which I won’t bore you with now, but I noticed that he was unconvinced, even puzzled. I do think that this represented a moment when the Catholic-Protestant division emerged clearly. Luther and his followers rather consciously stepped away from the beautiful, seeing it as a possibly idolatrous distraction, and opted for a more austerely word-centered approach to the Gospel. I then asked Dr. Craig, a bit playfully, to name what he liked most and least about Catholicism. In regard to the latter, he mentioned a number of classical sixteenth-century concerns about certain Catholic doctrines, and in regard to the former, he said that he greatly admired the rich and long intellectual tradition of Catholicism, stretching back from modern times, through the medieval doctors, to the Fathers of the Church.

The evening ended much too quickly—at least as far as I was concerned. We had staked out a good deal of common ground in our shared struggle against a secularist ideology that is rigidly set against religion. But what I found most uplifting about the session was that a Protestant and a Catholic—both committed to their respective traditions—could come together in fellowship, good cheer, and mutual support. That in itself filled me with hope.

Editor’s Note: Bishop Barron’s article first appeared January 23, 2018 on the Word on Fire website and is presented here with the kind permission of the author. For a video recording of the evening, view this article on Word on Fire.