How the first Selfie leads us to Christ!

by Mark Armstrong | April 4, 2017 12:04 am

Holy Mass celebrated before the Shroud of Turin,

Photography by Mark Armstrong

I have been blessed to pray and attend Mass before the Holy Shroud of Turin in both 2010 and 2015.

Today, The Holy Shroud or La Santa Sindone is out of public view at Duomo di Torino; Cattedrale di San Giovanni Battista or the St. John the Baptist Cathedral in Turin (Torino), Italy. There are no scheduled public exhibitions. Never did I imagine I would be among the two million pilgrims who came from all over the world to look at the Man in the Shroud on two occasions.

In 2010, our fourteen-year-old daughter Teresa and two of her friends accompanied me.

And in 2015, Teresa came back with four of her brothers and sister, along with Patti, my bride of thirty-five years.

In fact, I first heard about the Shroud the year Patti and I were married in 1981. Since then, I have dug deep into the mystery, history and science of this remarkable relic that has been venerated for centuries. Over the years I have read and learn much about The Shroud and one other remarkable Church relic the Sudarium of Oviedo, believed by many to be the Facecloth that covered our Savior’s head from the Cross to the Tomb.

In the years since my original trip to Turin, Italy, I have spoken before schools and groups with a PowerPoint presentation that delves into what this enigmatic image on this ancient cloth tells us about the sufferings of Jesus Christ. While the presentation is available on YouTube[1], I cannot get into much of the remarkable details in thirty to sixty minutes. So for those who like longer stories or articles, feel free to keep reading. Or, if you want skip to the end for greater resources than this article on what I know about The Holy Shroud of Turin.

What is known about the Shroud of Turin?

[2]

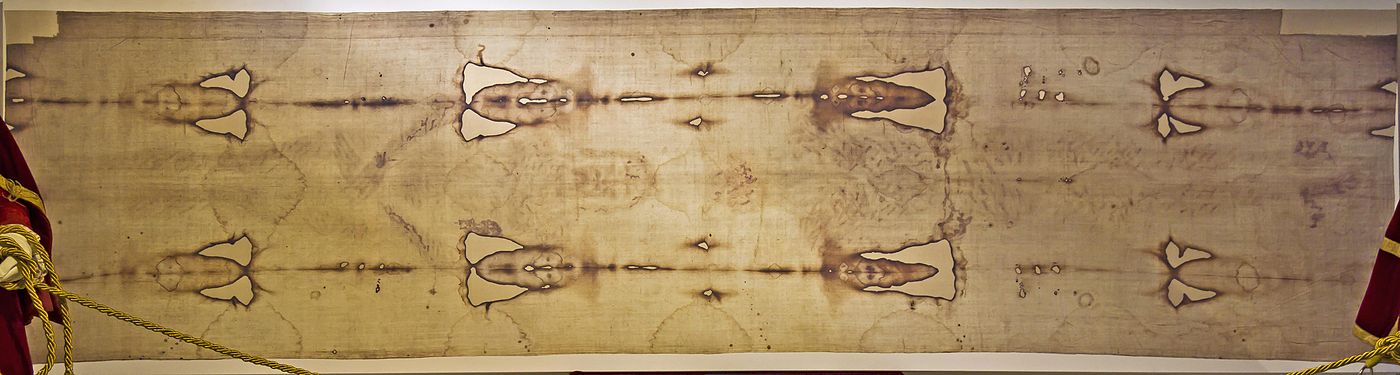

[2]The Shroud of Turin,

Photography by Mark Armstrong

For those who are a little unsure of what the “Shroud of Turin” is, let me give you a very basic description and the rest of the article will tell you what I have learned in the last thirty-five years. The Shroud is a gruesome reversed photograph of a man murdered on a cross. As Catholics, we would never have to believe that Shroud is truly the one placed on Our Lord when he was prepared for the tomb on Good Friday. The Church is careful not to give an outright endorsement—no more than it would to any other of its treasured relics. And yet when Pope Benedict XVI himself paid a visit to Turin in 2010, he remarked that the Shroud is an icon, “written with the blood of a crucified man in full correspondence with what the Gospels tell us of Jesus.”

Similarly, when Pope Francis venerated this ancient relic silently in prayer for several minutes and then he commented at the Mass in 2015, “The icon of this love is the Shroud that directs people toward the face of every suffering and unjustly persecuted person.”

Are there other burial cloths?

Learning more about the history of The Shroud drew me to learn more about the Sudarium of Oviedo, Spain as well. This is believed to be the actual facecloth placed over Christ’s head as he was laid out in the tomb. Some think the Shroud of Turin only could date as early as 1190 because of the infamous 1988 carbon-14 dating test (that was later discredited). The history for the Sudarium in Oviedo, Spain is known more reliably. The Sudarium was inside a chest of relics whisked away from Jerusalem when it was conquered by a Persian king in the seventh century. The chest, with the Sudarium, ended up in several Spanish cities, being carried northward for safety as the invading Muslim armies took over southern Spain in the eighth century, eventually ending up in extreme northern Spain at Oviedo in 840.

The chest with the Holy Relics was not even opened until the eleventh century. For three centuries, a huge chest containing relics from the Holy Land was venerated, but the contents were only passed down orally through the centuries because contents were deemed too holy to be seen. No one dared opened the chest for over three hundred years.

Finally, there was a King of Spain, Alfonzo VI, who decided it was time to open the chest of relics that had sat in an enclosed altar for over three hundred years! After many days of prayer, fasting and the wearing of sackcloths, King Alfonso VI had the chest opened and a catalog made of what was inside.

One of the items was the Sudarium, the bloody cloth that was placed on Jesus Christ when he was laid out in the tomb. The key biblical passage is, John 20:6-7, “Simon Peter, following him, also came up went into the tomb, saw the linen cloth (The Shroud of Turin) lying on the ground, and also the cloth that had been over his head (The Sudarium) that was not with the linen cloth but rolled up in a place by itself.” [italicized notations added].

Like the Shroud, the Sudarium has been studied by science. Scientific studies have shown that the Sudarium and the Shroud were in contact with the same AB blood. If either is a forgery, they date to the eighth century at the very latest, not the twelfth century the 1988 carbon-14 test indicated.

There are over one hundred-twenty points of match between the blood wounds on the Sudarium and the Shroud. With a complete match for the cap of thorns placed on Christ’s head. The best explanation for why there is no reversed image on the Sudarium like the Shroud is that it was likely removed before Jesus was shrouded. It explains why it was folded and not with the linen cloth when Peter and others entered the tomb.

The Sudarium of Oviedo measures 40 by 24 inches and is kept in the Cathedral of Our Savior in a small chapel that was built especially for the chest of relics in 840 in Oviedo, Spain. It is brought out on display three times a year. Good Friday, the Feast Day of the Triumph of the Cross, September 21, and its octave, September 28. This is the feast date, celebrated since the fourth century, in which the Church celebrates St. Helen’s miraculous discovery of pieces of the True Cross when she went on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Originally among the relics inside the chest on Oviedo were pieces of the True Cross.

What Do we Know about the History of the Shroud of Turin?

Photographic Negative of Holy Face on Shroud,

Photography by Mark Armstrong

The Shroud of Turin is 14 by 3.3 foot-wide linen cloth that bears the faint image of a crucified man. Millions believe that man to be Jesus Christ. It is said to be the most scientifically studied Church relic ever. And still the origin of this image is debated among scientists, historians and theologians. While no one would ever be required to “believe” that the Shroud of Turin is the actual burial cloth of Jesus Christ, one thing is clear: to this day none of the skeptics can accurately tell us how this bloodstained, linen cloth came to bear the image of a photographic negative of a crucified man.

There is clear and convincing proof in the body of scientific evidence in favor of the belief that the Shroud is the actual burial cloth of Christ. Ever since 1898 when Italian photographer Secondo Pia discovered that the image was actually reversed, as in a photographic negative, scientists have attempted to unravel its mysteries. The more we peel back its layers, the more mysterious the Shroud becomes and lives up to one of its earliest descriptions when it was known as “an image not made by human hands.”

During both our trips to Turin, I was able to tour several museums and get my hands on several excellent reference guides about the Shroud and its history. Here’s what scholars tell us are the places the Shroud has been from the known historical records. (This is taken from references which are listed on the end of this article).

This description of “an image not made by human hands” first comes to us in references about an ancient cloth said to bear a facial image of Jesus Christ. It was known as the Image of Edessa, the Edessa Cloth and later during the Byzantine Era as the Holy Mandylion. Edessa was a great city during the time of Christ, now known as Urfa in modern day Turkey. There is a high level of certainty amongst scientists, religious scholars and historians that the Shroud of Turin is the cloth referred to as the Image of Edessa.

It is said that this facial image on a cloth came to Edessa to King Abgar V Ouchama of Edessa (13-50 AD) by the Apostle Thaddeus. This was documented in Eusebius of Caesarea’s early 4th century Ecclesiastical History. He writes about a document once in Edessa’s archives that had been written by King Abgar V and delivered to Jesus by an envoy. The King asked Jesus to come to Edessa and to cure him of leprosy. The history reports that the Apostle Thaddeus was sent sometime after Jesus’ death and that he founded a church in Edessa.

A separate Syrian manuscript, the Doctrine of Addai, confirms these details and adds that a “portrait” of Jesus accompanied Thaddeus. It referred to the Edessa Cloth as a “tetradiplon.” A tetradiplon means a cloth doubled in fours, so that only the face in the cloth is visible. King Abgar was cured of his leprosy. Following the King’s miraculous cure his kingdom was converted to the new Christian faith. Others comes to see this Image of Edessa and are converted as well over the centuries (much in the way Our Lady of Guadalupe would convert millions centuries later in the New World).

But after four centuries the people begin to lose their faith and those who were in possession of this Image hid it inside the walls above one of the city gates in Edessa. They were fearful that it would be destroyed. The cloth was eventually lost, or forgotten about, until the year AD 544 when it was rediscovered during a Persian invasion and placed in a new Church built especially for it. In the late sixth century Evagrius Scholasticus’ Ecclesiastical History mentions that Edessa was protected by a “divinely wrought portrait” sent by Jesus to King Abgar.

In AD 730, St. John of Damascus, in his book On Holy Images, talks about the cloth as a “himation,” which is translated as “an oblong cloth or grave cloth.” This is the first time it can be ascertained that the historical references are not simply referring to an image of the face of Jesus, but in fact an entire image of the crucified body of Christ.

In AD 944, there was an attack on Edessa again, this time from Muslim invaders. The Cloth of Edessa was transferred to Constantinople, the Byzantine capitol city now known as Istanbul in Turkey. When the image arrived the Archdeacon of the Hagia Sophia Cathedral preached a sermon about the cloth being a burial cloth, believed to be that of Jesus and that it contained bloodstains. There are several historical documents that referred to the Image over the next two hundred-fifty years.

In 1204, the Shroud disappears from Constantinople when the city is sacked by Knights of the Fourth Crusades. The Knights seized numerous relics because of the invading Muslims and once again removed the Shroud. In 1207, Nicholas d’Orrante, Abbott of Casole and the Papal Legate in Athens wrote about the relics taken from Constantinople by the Knights and referred specifically to the Shroud saying that he saw it “with his own eyes” in Athens.

A French knight, Geoffrey de Charny, was the first identified owner of the Shroud after this time and he wrote to Pope Clement VI that he wanted to build a church at Lirey, France for the Shroud. The year was 1354. Large crowds came to visit the church at Lirey to view the Shroud and special medallions were struck. I saw one of these original medallions at the Turin Museum and it depicts an image of the Shroud. The Shroud remained in the de Charny family for about one hundred years until it passed to the Savoy family.

By 1532, the Shroud had been moved to several different locations for security and veneration reasons. That was the year the Shroud suffered fire damage in the St. Chapelle Chapel in Chambery, France. It had been located there since 1453. Burns to the cloth resulted from molten silver from the reliquary box in which it was stored and produced symmetrical marks in the corners of the folded cloth. Poor Clare nuns attempted to repair this damage with patches. There were also a number of water stains caused by the extinguishing of the fire.

In 1578, the future Saint and then Cardinal Charles Borromeo, wanted to take the dangerous journey on foot, over the Alps, from Milan, Italy to Chambery, France to give thanks in front of the Shroud in thanksgiving for Milan having been mostly spared from the ravages of the Plague. To save Cardinal Borremeo such a journey across the Alps, the owners of the Shroud ordered that it be transferred to Turin. It has remained in Turin ever since.

What do we Know about the Science of the Shroud?

It would take several books or websites to get into all the scientific testing that has been done on the Shroud of Turin. (And there are, indeed, several source websites devoted to the science of the Shroud, posted at the end of this article). Suffice to say that the real testing began in 1978 when several scientists were given access to Shroud for five days. It is known by the acronym, STURP or Shroud of Turin Research Project.

For one hundred-twenty hours in 1978, the STURP scientists photographed, x-rayed, pressed sticky tape, took samples from the bloodstains, did spectra analysis tests and snapped thousands of photomicrographs of the Shroud. Three years later they released their findings, and more than thirty years later their study has not been notably contradicted. It remains the gold standard in Shroud testing. The results can be found on the websites below. Each year new papers and theories are shared amongst those who still study the Shroud.

Among the STURP findings: No pigments, paints, dyes or stains were found on the fibrils of the linen cloth. It is not a painting. An image analyzer shows the Shroud has a unique, three-dimensional codex embedded in it, unlike any other two-dimensional image made by humans. While some explanations of what caused the image on the Shroud are possible from a chemical point of view, there are precluded by physics and certain physical explanations are conversely completely precluded by the chemistry. To explain the Shroud image there must be a complete explanation from a physical, chemical, biological, and medical standpoint. To date no one has presented this complete solution. It is an enigma.

The best scientific explanation is that the Shroud image was produced by something which resulted in “oxidation, dehydration and conjugation of the polysaccharide structure of the microfibrils” of the linen itself. STURP concluded that for now that the “Shroud image is that of a real human form of a scourged, crucified man. It is not the product of an artist. The blood stains are composed of hemoglobin and also give a positive test for serum albumin.”

The scientists also determined that there is evidence on the Shroud to show that it has pollen on it that can be traced to all the known locations at the specific times in its history: from Jerusalem to Edessa to Constantinople to Athens to locations in France and Italy.

In 1988, carbon-14 tests seem to indicate that the cloth was dated to between AD 1190 and 1350. This led some to believe it was a clever medieval forgery. But since that time those results have been called into question on a number of levels and now the carbon-14 tests themselves have been largely discredited.

Final Reflections on our Days in Turin in 2010 and 2015

In Fromt of St. John the Baptist Cathedral in Turin,

Photography by Mark Armstrong

On our last trip to Turin, we went to Mass at the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, where the Shroud would be venerated by two million people in the spring of 2015. The Cathedral is one of the fifty-four Catholic churches that are nearly everywhere you walk in old Turin.

May 13, 2015 was already a special day for the Armstrong family. That morning, on the feast of Fatima, was my fifty-ninth and our son Jacob’s twenty-fifth birthdays (one of three Armstrong shared-birthdays in our family of twelve).

We joined the one hundred-fifty or so people inside the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist for the daily Mass in Italian. We were surrounded by the faithful, including many nuns, deacons and priests. It was a profoundly moving experience for all of us. My lovely bride Patti commented as we left the Cathedral, “It is really amazing to think of all the people throughout the last two thousand years, starting with Mary Magdalene, and then the Apostles, who have seen the Shroud.”

In the afternoon we shopped for some Shroud holy cards, medals and artwork to bring back for some of our friends and family. There at the Apostolato Liturgico gift shop run by an order of nuns, we talked to Sister Chiara Noventa[3]. With six of our kids present, she commented on what a large family we had brought to the Shroud. She was genuinely shocked when I told her four of our adult children were unable to make the trip. “I will pray for you and your beautiful family,” she promised.

Our next stop was to tour both way below and then way above the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist. Mass was first said here in the early fourth century. The original church was built upon the ruins of a Roman amphitheater, the stones of which were still visible in the basement of the cathedral. Next, it was time to climb to the very top of the church bell tower, which was constructed in the late fifteenth century. The views of the city of Turin from atop the bell tower were stunning. There are so many Catholic Church steeples that were visible along the Turin skyline that it was hard to count them all.

In fact, there are fifty-four Catholic churches inside the walls of the old city of Turin, most dating from the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries. You cannot walk more than a couple of blocks without finding a church. At one location at the Piazza San Carlo, there were two Churches across the street from one another. From the outside, St. Charles Borromeo and St. Cristina looked like nearly mirror images of one other. Inside all of Turin’s churches were large gold leaf-framed pieces of art, marble statues and columns, plus beautiful, elaborately-decorated tabernacles. Sadly, many of these churches no longer offer Masses because, while the population of Turin today is nearly one million—nearly ten times what it was in 1861 when it was Italy’s first capital city, few attend Mass or any services anymore. The same is true all over Italy and Europe.

After a double birthday dinner at the nearby steakhouse, “The Jumping Jester,” we walked to the riverfront and then enjoyed some gelato again. While there may not be crowds inside many of Turin’s churches these days, there were people aplenty watching television outside and inside of bars and restaurants showing a soccer match between Turin’s team, Juventus, against their archrivals Real Madrid. Car horns and cheers could be heard throughout the city until the early morning hours as they home team pulled out a 2-1!

The Shroud remains at the Cathedral in Turin, but it is not another scheduled public viewing. Many wonder, “Why is the Shroud not always on public view?”

There are many answers to that question. Under law from the time of Christ’s death until really the Middle Ages, the mere thought of possessing or beholding the actual bloodstained burial cloth of Our Lord would have been repugnant. At the time of Christ’s death under Jewish law you were forbidden to posses burial cloths, and we know other contemporary societies in ancient times had similar customs. Early Christians probably knew the Shroud and other burial cloths (like the Sudarium of Oviedo in Spain) would be destroyed by early persecutors of the faith. The fact that pilgrims continue to come to Turin even when the Shroud is out of public view attests to its authenticity with the faithful. They cannot see it; they just want to be where the Holy Shroud is kept reverently.

As noted earlier in this article, it will never be a requirement for those in the Catholic faith to accept that the Shroud is the true burial cloth of Jesus Christ. We know there was a linen cloth 2,000 years ago that was used to bury our Lord as He was laid in the tomb. Science has not been able to replicate this bloodstained Shroud precisely or prove that it is not what it is purported to be. Saint John Paul II said, “it is the Image that everyone can see and no-one can explain.”

Additional resources for the Shroud of Turin:

- www.Sindone.org[4] (the official website in Turin)

- www.Shroud.com[5]

- www.ShroudofTurin.com[6]

- www.ShroudStory.com[7]

Please share on social media. [8]

[8]

- YouTube: https://youtu.be/4JnAhr1C5Og

- [Image]: http://www.integratedcatholiclife.org/wp-content/uploads/arnstrong-shroud.jpg

- Sister Chiara Noventa: http://www.apostolatoliturgico.it/curriculum/chiara-noventa.aspx

- www.Sindone.org: http://www.sindone.org/

- www.Shroud.com: http://www.shroud.com/

- www.ShroudofTurin.com: http://www.shroudofturin.com/

- www.ShroudStory.com: http://www.shroudstory.com/

- [Image]: http://www.integratedcatholiclife.org/donate/

Source URL: https://integratedcatholiclife.org/2017/04/mark-armstrong-how-the-first-selfie-leads-us-to-christ/