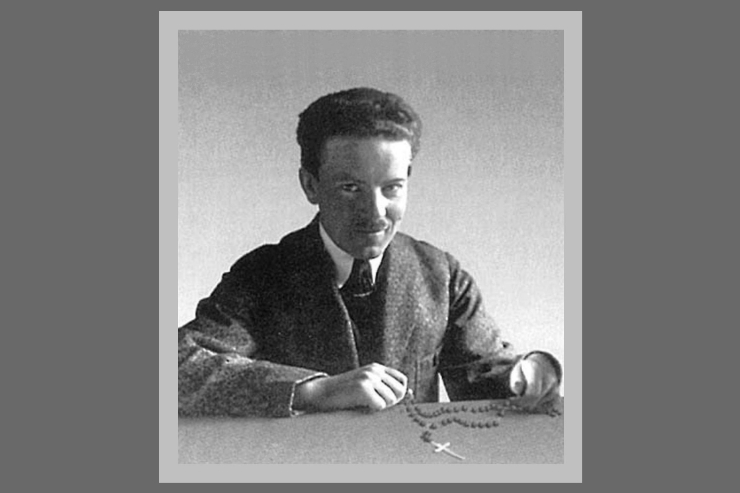

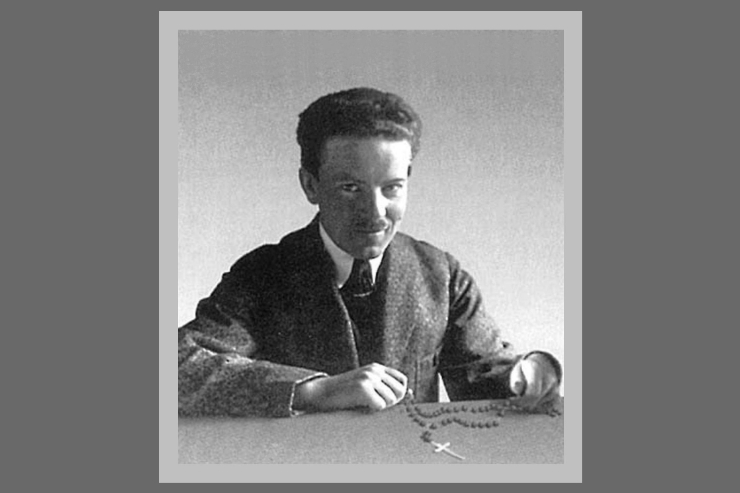

Venerable Jan Leopold Tyranowski (1940)

For those who love St. John Paul II, Saturday, January 21, 2017 was a big family celebration, when Pope Francis authorized the Vatican’s Congregation for the Causes of Saints to promulgate the decree of heroic virtues for Jan Tyranowski (1901-1947), the Polish tailor who played an indispensable role in helping the young Karol Wojtyla become a man of prayer and apostolate and assisted him to discern his priestly vocation. Without Jan Tyranowski, there likely would never have been John Paul II, and his life provides a compelling witness of lay sanctity that deserves to be better known and emulated.

In Jan we see a model of adult conversion from spiritual mediocrity to the holiness to which God calls each of us. He was a nondescript 34-year-old used to fulfilling his religious duties but not much more when he heard a homily in which one of the Salesian priests at St. Stanislaus Kostka Parish in Krakow emphasized, “It’s not difficult to be a saint!” They were revolutionary words at the time for a layman, because it was presumed that if one wanted to become holy, the path was as a priest or religious. That an accountant-turned-tailor not only could become holy but could do so in his day-to-day life was a thought that changed his life.

He began to go to daily Mass. He started to attend various parish events and adult education opportunities. He joined Catholic Action, a group to help lay Catholics transform society. He commenced reading good Catholic books. He consulted priests. He became a man for whom prayer became the defining reality of his life. He made a vow of chastity, despite interest in marriage from several women. In short, he became serious about his faith, about his soul, and about the direction of his life.

That led him to form a plan of life to grow in faith and live by it. As a trained accountant he was accustomed to care for small details and he formed a business plan for the enterprise of his soul and began to keep a meticulous profit-and-loss ledger of his spiritual life. He woke early, attended Mass, did spiritual reading and prayed the Rosary before breakfast, followed by reading of Sacred Scripture. Then he did several hours of work as a tailor — the profession likewise of his father and grandfather that he adopted after a stomach ailment and eventual tuberculosis impeded his accounting work — contemplating as he sewed the way the soul needs to be dressed with faith, hope and love. After dinner, he would pray the Angelus, meditate and do spiritual reading before retiring at 8:30, giving him enough rest before awakening early the next day.

Seeing the change in him and the discipline with which he began to take his interior life, one of his parish priests said he was acquiring the virtue of a great athlete, dubbing him, because of the long prayerful hikes he would take, a “spiritual mountaineer.”

Even though he was an extreme introvert, he eventually forced himself to overcome his temperament in order to pass on the fruits of his contemplation to others. After the Nazis invaded Krakow in 1939, they deported and killed in the concentration camps a third of Krakow’s clergy, including 11 of the 13 Salesians at Jan’s parish, leaving only two elderly clerics behind. There was no way these two priests alone could continue to pass on the faith to the young at a time a severe crisis. They needed help. Jan was at first reluctant, deeming himself too shy and incapable, but the desperate priests prevailed.

So he started to form Living Rosary cells, groups of 15 young men, each of whom would commit to praying one specific decade of the Rosary each day so that, together, they would recite the entire Rosary for the needs of each member and for the enormous needs and intentions of their people under Nazi occupation. The men would commit themselves to supporting each other as spiritual brothers. Once a week, the leaders of each Living Rosary cell would get together with Jan Tyranowski for a class on prayer and the spiritual life, as he would share with them the thoughts of St. John of the Cross, St. Teresa of Avila, Adolphe Tanquerey and others. He would pass on to them the way to grow in faith so that they, in turn, could better form the others in their group. He would also offer them some individual spiritual direction, where he would suggest spiritual reading, review with them what God was communicating to them in prayer, and nurture their souls.

It’s noteworthy that it was only because of the dramatic reductions in the number of priests that his extraordinarily fruitful apostolate was unleashed.

It’s also, I think, not a coincidence that from the young men he formed through the Living Rosary, exactly 11 became priests, essentially taking up the torch of the 11 Salesians whom the Nazis had rounded up and executed.

Among those he recruited and made a leader of a Living Rosary group was Karol Wojtyla. Tyranowski was the one who introduced him to St. John of the Cross, whose writings would dramatically influence the development of his mind and soul and on whom he would write one of his two dissertations. The two would get together often in Jan’s apartment for spiritual direction. Jan would accompany him on his long walks to the Solvay Chemical Plant where the future pope and clandestine seminarian did manual labor during the occupation.

John Paul, who retained a picture of him in his bedroom for the rest of his life, said about him, “He was one of those unknown saints [who]… disclosed to me the riches of his inner life, of his mystical life. In his words, in his spirituality and in the example of a life given to God alone, he represented a new world that I did not yet know. I saw the beauty of a soul opened up by grace.”

His own soul would likewise be opened.

Jan, whom he called an “apostle of God’s greatness, the beauty of God, the transcendence of God,” would help him to see that the Christian life was not a bunch of rules, but ultimately a participation in very life and love of God. He helped him to grasp that this was the meaning of a holy life and to become a saint was not difficult if one opened oneself to God and willed the means.

That was an understanding that the future Saint Karol Wojtyla would eventually take to the chair of St. Peter as he promoted throughout the Church, and in particular through so many beatifications and canonizations, the universal call to holiness of life he had learned from Jan.

Jan would die of tuberculosis at 46, soon after Wojtyla’s priestly ordination. But he would, in a sense, get an assist on every soul the priest and future pontiff would impact.

As Tyranowski is advanced on the road toward canonization, his life is a potent reminder that sanctity is in the reach of everyone whose soul is open to grace.

This article originally appeared in The Anchor, the weekly newspaper of the Diocese of Fall River, Mass, on January 27, 2017 and appears here with permission of the author.