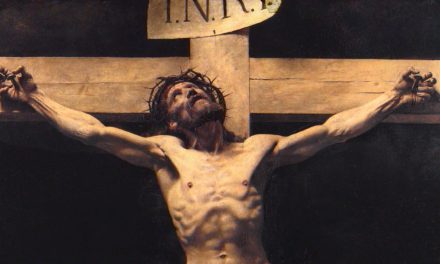

Saint Augustine and his mother, Saint Monica

This weekend we celebrate back-to-back feast days of two great saints, Monica and Augustine. There are few saint stories as legendary as this one: the mother who prays for decades for the conversion of her son, who is very intelligent but also very worldly; the son who is the prototype for so many converts as he endlessly searches for truth in various places, and even upon finding it, struggles with the virtuous life that must accompany it. Countless people throughout the centuries have found consolation in their story—mothers who join Monica in tearfully pleading to God for their family members, intellectuals who search for truth, or simply the average Christian who struggles against temptation to become a saint.

My favorite part of Augustine’s Confessions comes at the end of Book IX, when he recounts Monica’s death and the days immediately following. Augustine struggles with his emotions of grief and the tears he wants to shed after his mother’s death. Is it proper to show such emotion, when he knows Heaven is better than this earth? He knows Christ has defeated death, and, convinced of her holiness, he knows she will rest in peace. So is his sorrow a lack of faith?

He finally allows himself to cry and receives consolation in allowing his heart to grieve for the human loss of his mother, who had become his constant companion.

“Little by little I recovered my earlier thoughts about your handmaid, remembering how devout had been her attitude toward you, and how full of holy kindness, how willing to make allowances, she had been in our regard; and now that I was suddenly bereft of this I found comfort in weeping before you about her and for her, about myself and for myself. The tears that I had been holding back I now released to flow as plentifully as they would, and strewed them as a bed beneath my heart. There it could rest, because there were your ears only, not the ears of anyone who would judge my weeping by the norms of his own pride. And now, Lord, it is in writing that I confess to you. Let anyone read it who will, and judge it as he will, and if he finds it sinful that I wept over my mother for a brief part of a single hour the mother who for a little space was to my sight dead, and who had wept long years for me that in your sight I might live—then let such a reader not mock, but rather, if his charity is wide enough, himself weep for my sins to you, who are Father to all whom your Christ calls his brethren.”

He ends Book IX with a prayer for his mother, just as she had commanded him to do. It is common today to want to canonize our loved ones when they die. It is tempting to fall into this as we attempt to find words of consolation. In order to comfort the grieving loved ones, we extol all the virtues of the deceased and we assure the family that their loved one is in heaven.

We can learn from Augustine, however. Notice what he does. After he comes to grip with his sorrow and realizes it’s not wrong to grieve after this human loss, he turns to pray for his mother’s soul. He extols her and proclaims her virtues, but he is not afraid to admit that she has sinned and that she requires God’s mercy. It is a false comfort to tell ourselves that our loved one has gone immediately to Heaven. It may make us feel better in the short term, but if our loved one is indeed in purgatory, they would much rather have our prayers than our praise.

He recognizes the legitimacy of his grief, but he answers this grief with the greatest gift he can give to his mother: his prayers. Her last request was that he remember her soul in his prayers, and he obeys her. He pleas for her soul to God, and he urges anyone who reads his Confessions to pray for her soul and the soul of his father, Patricius.

“Let them remember with loving devotion these two who were my parents in this transitory light, but also were my brethren under you, our Father, within our mother the Catholic Church, and my fellow citizens in the eternal Jerusalem, for which your people sighs with longing throughout its pilgrimage, from its setting out to its return. So may the last request she made of me be granted to her more abundantly by the prayers of many, evoked by my confessions, than by my prayers alone.”

Monica spent years weeping over the sins of Augustine and praying for his conversion. It is only fitting that he in turn weeps for the loss of his mother’s companionship and prays for her soul. We should all follow their example. Our prayers are the greatest things we can give our friends and family—before and after death.