“The Holy Cave” where Our Lady of Covadonga appeared to Pelayo

I never used to like history. Then one of my best friends introduced my husband to a book that was more story than history book. My husband read it in record time, which was remarkable given his limited reading time and his tendency not to read for pleasure.

On the other hand, I am a bookworm of addictive proportions. My nose is happy as long as there’s a book attached to it, and I’ll try just about anything. When I call reading a hobby, I’m understating the case: I have reordered my life more than once when reading time has gotten too low to sustain my love and—dare I say it?—need for it.

It’s not surprising, then, that I was unable to resist reading this book, The Frontiersman, by Alan Eckert, though it was a monolithic five hundred and eighty-eight pages of teeny, tiny print, with Ohio history as its subject.

I flinched, I hesitated, I complained a bit. My husband shrugged. He had no doubt of the pull those unread pages would have on me. He knew I couldn’t resist the siren call of a book he had loved, one that I hadn’t read.

This book pulled me in from the very beginning and kept me captivated until the last word. I stayed up late, I got up early, I lugged it around from kitchen to living room and in the car. I could think of little other than Simon Kenton’s adventures. I was on the edge of my seat, because I didn’t know what would happen next.

More than once, I looked up at my husband, incredulous. “This is history? This really happened?” I would exclaim, a question mark at the end.

I honestly never knew history could be so interesting. Maybe I should have stayed awake in high school, but some combination of the teacher and the text just turned off my brain. In college, I begged my advisor to let me take science courses instead of history. He argued that history was easy, but he couldn’t talk me out of it. I was only able to get away with this because of the heavy honors curriculum I was taking.

I don’t think, though, that college history would have changed my mind. I think it took a book that was alive and real, one that captured my imagination with its writing and subject.

We have driven to many of the places in Ohio where Simon Kenton had his adventures. We’ve talked about it and we’ve gone online and dreamed about taking time off to just meander through the state. I think, someday, we will do this. We’ll probably take our copy of The Frontiersman with us too, making notes and dog-earing the pages.

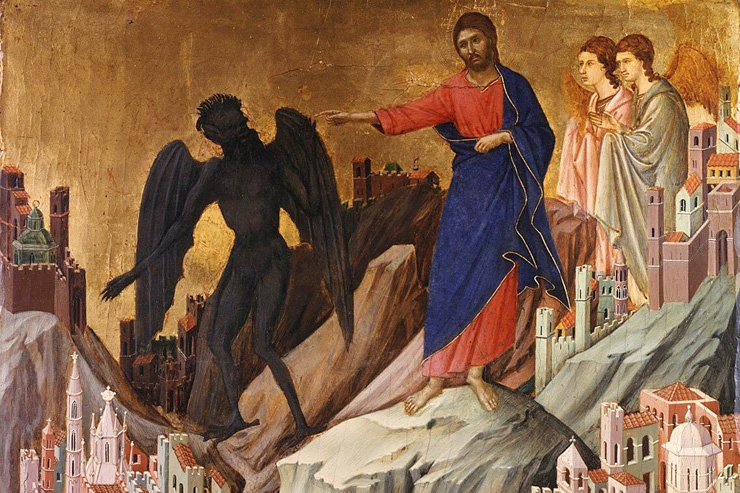

When I began researching Our Lady of Covadonga, I found a story that was no less compelling than the tale of Simon Kenton in the wild frontier of early Ohio. It all started long ago, in 711, when Islam was on the rise in Asia Minor and North Africa. The Moors turned their attention to Spain, and because the Visigothic kingdom was weak, the troops landed easily area of present day Gibraltar.

I don’t know what it would have looked like, the Moors and the Visigoths duking it out, one group defending their homeland, the other seeking to conquer and rule. The Visigoths lost the battle and King Rodrigo was killed. He was obviously a hero to his people, though, because legends immediately cropped up that, on the one hand, he had not died, but had become a hermit, and on the other hand, that if he had not died, he appeared in another form to strengthen his people.

What was left of King Rodrigo’s Visigoth army panicked, separating to many different places. Don Pelayo, a relative of King Rodrigo, remained undaunted by the defeat. I picture him as a fierce man, forced to live in the maze-like caves in the hills and mountains of Asturia. He was certainly unhappy about it, but I have a picture of him as a hero, a tough guy who loved his country so fiercely he wasn’t going to give up and let the Moors have an easy victory over everyone.

When you’re in hiding with an army, there’s not a lot of room for discord. Shortly after arriving at the hiding place in the caves near Covadonga, Don Pelayo was going to discipline a member who had fled the group and been marked as disruptive. Just as Don Pelayo was going to take him prisoner, a hermit appeared before him and informed him that the cave before him should be honored as a sanctuary and that the fleeing offender should be granted asylum. The hermit told him, “If you pardon the culprit now, you will find haven one day at the same spot and thus remake the Empire.”

Was Don Pelayo startled by the hermit’s insistence and obvious holiness? Could he recognize the truth in the hermit’s prophecy? Was the dream of remaking the empire more than he could ignore? Don Pelayo would have been aware that the cave the hermit referred to had been considered a sanctuary of Mary for as long as anyone could remember, drawing hermits and others to venerate an image that was there. Whatever the reason, Don Pelayo pardoned the man, though I imagine there was a warning attached.

It took seven years of hiding in the caves and hills for Don Pelayo’s rebels to prepare for their attack. In 718, the Moors had had enough of the rumors of an army building in the hills, and they sent an entire army into Asturia with instructions to get rid of the hiding Visigoths once and for all.

Even though Don Pelayo was a brave leader, I’m sure there was a little bit of sweat under his armpits when he heard than an entire army was coming his way. He did the wisest thing he could: he went to the cave where he had met the hermit and prayed there.

The image of Don Pelayo’s band meeting the immense Arab army is the stuff Hollywood loves. I can hear deep music and smell the tension in the wind. More than one of Don Pelayo’s men must have offered up a desperate plea to heaven, and perhaps it was this desperation, this sense that they had nothing to lose, that gave them a glint in their eyes.

The Moors must have chuckled to themselves when they saw how much they outnumbered Don Pelayo’s group. Did they laugh? Did they jeer before they started shooting arrows? Were they certain of their victory?

As the arrows blackened the sky and lances and darts were thrown, things looked bleak for the Visigoths. How would they survive this onslaught? Then, probably with a feeling of confusion, the attacking Moors realized their weapons weren’t reaching the band of soldiers in the hills. Everything was bouncing off the rocks. How could that be?

Don Pelayo’s party must have been felt a surge of hope, and it must have been just what they needed. I can just see them laughing and then attacking the Moors. The Moors were confused, unsure of what was happening, and in that confusion, they fled, pursued by the small Visigoth army. As they headed for the safety of the Mount Auceva plains, a huge thunderstorm erupted, causing the river Deva to overflow its banks and a landslide to form, crushing the fleeing army.

Don Pelayo’s victory was decisive, though the majority of Spain was still under Moorish control. He became the king of Asturia, and saw to it that the remaining Visigoths joined with the Hispano-Roman tribes, shaping the beginning of historic Spain. The Virgin of Covadonga has been one of the landmark symbols of the Spanish nation, and the cave at Covadonga is revered as a holy sanctuary.

Our Lady of Covadonga took the efforts of the soldiers and multiplied them. There they stood, on the cliffs and hills, with a mighty force before them.

Are we so different? Before us lie the temptations of the world, the attacks of consumerism and greed, the constant questioning of our values and ethics. Yet, Mary reminds us, as Our Lady of Covadonga, that though we seem to be outnumbered and overwhelmed without a shot at victory, that we aren’t alone.

We don’t have to solve all of our problems—or the world’s problems either—by ourselves. It’s easy to think a case is hopeless, whether it’s the cleanliness of our house or the salvation of our souls.

Before we give up, though, let’s turn to Mary, Our Lady of Covadonga. Let’s stand on the mountain and watch the arrows bounce off the rocks around us.

In Our Lady of Covadonga, I see hope for myself and hope for the world. In the rich history of the title, I enjoy an adventure that holds a lesson for me. Though the enemy is fierce, though the battle is long, though I am weary, I’m not alone.