Sometimes—often—in my Christian journey, I have discovered that God’s timeline is different than mine. While I’m busy praying every prayer I can find, He’s at work. The problem, for me, is that I don’t always see results immediately.

“Hey God,” I call, “it’s been a week since I started that novena. I know, a few more days to go. But, well, would You mind sending me a little signal or something?”

The silence that greets me doesn’t annoy me quite as much as it used to. I’ve come to expect it; it’s part of the lesson in patience and trust that’s going to take me the rest of my life to learn well.

In an age of instant communication, maybe I’m not so different from everyone else. When I send an email, I can usually expect an answer that day, though I may not say so. When I call someone and leave a message, I know my phone will probably ring in a couple of hours with a return call. And those examples aren’t nearly as quick as the methods I’ve been avoiding lately—instant and text messaging. How can my expectations for God’s answers be any different, given the background of today’s world?

In Our Lady of Prompt Succor, I thought I had found a Mary who was on the express train of my modern day mentality. Prompt, after all, means “instant,” right? And “succor” is just another word for “help.”

“Woohoo!” I cheered to myself, “I have a new patron!”

Then I realized that Mary has been called Our Lady of Prompt Succor for almost two hundred years. Two hundred years ago, instant communication was possible only if you were in the same room as the person you were trying to reach.

Persistence, though, is a powerful motivator, and when coupled with miracles, it seems to grab God’s attention and be the secret ingredient behind miracles, sometimes even shaving the wait to nothing.

Our story of persistence—and the miracles it started—begins in 1727, when French Ursuline nuns arrived in New Orleans, Louisiana, and established a convent and the oldest school for girls. They educated all girls, European or Native American or Creole, slave or free.

The school grew and Spanish sisters came to help when the Louisiana Territory fell under Spanish control in 1763. Then, in 1800, when the territory was back in French control, most of the nuns fled to Cuba, fearing the anti-clerical mentality of the French Revolution, leaving only seven nuns at the school.

The nuns were not giving up, though the workload was enormous. After the death of Mother Saint Xavier Farjon, who was a mainstay within the community, though, Sister (soon to be Mother) Saint Andre Madier, wrote to France, asking her cousin, Mother Saint Michel Gensoul, for assistance in the form of more sisters.

Mother Saint Michel, headmistress of a Catholic girls boarding school in France, was having problems of her own as the effects of the French Revolution tore apart her country and her Church. Inspired by the Holy Spirit, however, Mother Saint Michel wrote her bishop, requesting a transfer to New Orleans to help her cousin.

Imagine how the bishop must have felt. His country was torn to pieces, with his Church persecuted at every turn, and a nun writes to him, asking to leave at a time when he can’t afford to lose one more from his flock!

“The Pope alone can give this authorization,” he told Mother Saint Michel. “The Pope alone!”

The situation was looking impossible for Mother Saint Michel: not only was Pope Pius VII in the far-off city of Rome and not only was the mail far less reliable and far less expedient then than now, but Napoleon’s soldiers had Pius VII cut off from the world, held prisoner as they waited to take him back to France. There was to be no communication for the Pope; the jailers had uncompromising orders. Writing to him was, more than anything else, an act of the utmost hope.

Initially, there was no chance for her letter to even leave France. Mother Saint Michel took her plea to the Blessed Mother, with a heartfelt promise that she would spread devotion to Our Lady of Prompt Succor if her request was met.

Her original letter was dated December 15, 1808. On March 19, 1809, it left France. On April 28, Pius VII had a cardinal send Mother Saint Michel a message approving her request and blessing her endeavors.

Mother Saint Michel kept her promise to Mary, and the statue of Our Lady of Prompt Succor, which is still at the Ursuline convent in New Orleans, came with her when she arrived in Louisiana in 1810. In the last two hundred years, Our Lady of Prompt Succor has been given credit for miracles that seem impossible, both for their immediacy and their apparent hopelessness.

Only a few years after her arrival in New Orleans, Our Lady of Prompt Succor was credited with a miracle.

A great fire was roaring through New Orleans in 1812. The Ursuline convent, home of Mother Saint Michel’s nuns, was right in the path of the fire.

Right after the order to evacuate—to give up—Sister Anthony found a small statue of Our Lady of Prompt Succor and, led by Mother Saint Michel, the nuns began to pray, “Our Lady of Prompt Succor, we are lost unless you hasten to our aid!”

At once, the wind changed direction, blowing the flames away from the convent. The fire was doused and the convent was safe. It’s no wonder that witnesses couldn’t help but exclaim, “Our Lady of Prompt Succor has saved us!”

A few years later, in 1815, the Ursuline nuns proved Our Lady of Prompt Succor’s concern by invoking her during the Battle of New Orleans. General Andrew Jackson had only six thousand American troops facing fifteen thousand British troops. Doom was in the air. Things seemed hopeless.

Perhaps remembering the command of the wind during the fire of 1812, many New Orleans residents joined the nuns in petitioning Our Lady of Prompt Succor. On the morning of January 8, amid the thunder of cannons, the priest offered Mass at the altar where, the night before, everyone had gathered before a statue of Our Lady of Prompt Succor.

At the very moment of communion, when the priest was consecrating the bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Jesus, a messenger arrived, informing everyone of the British defeat.

“The result seems almost miraculous,” the local newspaper acknowledged. “It was a remarkable victory, and it can never fail to hold an illustrious place in our national history.”

In our own times, Our Lady of Prompt Succor has had a hand in some unexplainable weather changes.

In 2002, Hurricane Lili was poised in the Gulf of Mexico with her Category 4 strength ready to bash New Orleans. Somehow, the storm dropped to a Category 1 right before it hit land. Hurricane center meteorologist Lixion Avila cited it as the subject of many future Ph.D. dissertations.

Though Hurricane Katrina made world headlines with the destruction in New Orleans in 2005, we would do well to look more closely at the results of what has been called the most destructive hurricane ever to strike the United States.

The day before landfall, Katrina was a Category 5 storm, with winds estimated at 175 miles per hour. On the day Katrina hit the coast, it was only a Category 3. And though Katrina made records as the most economically destructive storm, human losses were less than the Galveston hurricane in 1900. It’s guaranteed that many in New Orleans were begging Our Lady of Prompt Succor for her help during Hurricane Katrina—she’s invoked at every Mass and especially during the hurricane season.

You don’t have to live in New Orleans to invoke Our Lady of Prompt Succor. We all have needs that press on us with their urgency.

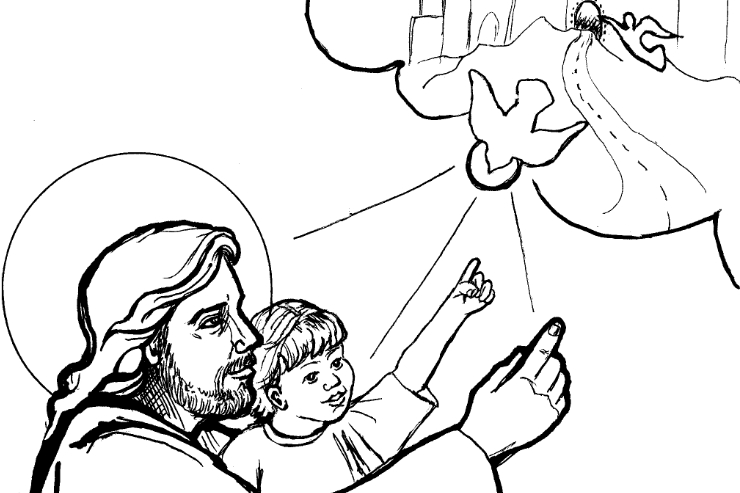

We can look to the statue of Our Lady of Prompt Succor, where Mary holds the child Jesus, both of them crowned in gold. Jesus is holding a small globe with a Cross on top. They are looking in different directions, keeping the world under their watch. The crowns tell us that they’re in charge, taking care of us, and we can rest easy knowing the whole world is in Jesus’ hands even as Mary, His mother, cradles us in her embrace with her Child.

It was as I reflected on the symbolism of this statue, on the visual impact it made on me, that I wondered, suddenly, if “succor”—the word I had equated with “help”—could mean more. Might “succor” also imply this motherly embrace? Could it lead me to reflect more about how I’m held as I wait for an answer to an urgent request? Was “succor” more than just a two-hundred-year-old way of saying “help”?

As it turns out, one of the longer definitions I found for “succor” has its roots in the Latin succurrere, “to run to the aid of.” As I read this, I thought of the time I fell down the stairs in our old farmhouse. They’re steep and tricky, nothing like the shallow, gradual inclines found in newer houses.

When my foot slipped halfway down, I was carrying my two-year-old daughter in my arms. I remember thinking only of my daughter, of how a crack on those wooden stairs could kill her. My first reaction was to shield her, and before I passed out, I asked my husband if she was OK. She was fine, and though I broke my arm, it was a small price to pay for my child’s safety.

Mary, as Our Lady of Prompt Succor, is holding Jesus close. He’s old enough to wiggle free, to drop the globe He’s holding. And though we know He never would, we can rest assured, knowing that Mary is holding Him, surrounding Him—and us—with her motherly embrace. In this image, we have a reminder that Mary will run to our aid in our need, that she will shield us in her arms and hold us close.

Though the divine timeline and mine aren’t always the same, encouraging me to continue to grow in patience and trust, I feel comforted knowing that, in those times of great and pressing need, there’s an image of Mary to hold me close.