From Faith Came Science: Condemnations of 1277

by Stacy A. Trasancos | February 4, 2015 12:01 am

[1]

[1]

In 1277, Étienne Tempier, the Bishop of Paris, issued a list of 219 condemned propositions relating to details of Aristotelian texts that were irreconcilable with the Christian worldview. These propositions were not binding on Christians, but served as a guide for the scholars at the University of Paris. The decree largely dealt with the eternity of the world and creation.

The Condemned Propositions

The propositions are often referenced by historians of science, and their intent and effects are disputed. It is instructive to review them as they are (in translation) and consider them on their own merit. Below is a list of some of the propositions condemned at the University of Paris by Tempier. [1] Note, the quoted material is a condemned error, not an assertion.

- Proposition 31 rejected that the heavens are divine. “That there are three principles for celestial things: the subject of eternal motion, the soul of the celestial body, and the first mover, [which moves things] insofar as [it is] desired. This is an error with respect to the first two.”

- Proposition 32 rejected that the world is an organism. “That the eternal principles are two, namely, the body of the heaven and its soul.”

- Proposition 66 said that rectilinear motion is possible for planets and stars. “That God could not move the heaven in a straight line, the reason being that He would then leave a vacuum.”

- Proposition 73 essentially condemned pantheism. “That the heavenly bodies are moved by an intrinsic principle which is the soul, and that they are moved by a soul and an appetitive power, like an animal. For just as an animal is moved by desiring, so also is the heaven.”

- Proposition 75 also condemned the animistic view of the universe as if the heavens are made of organs. “That the celestial soul is an intelligence, and the celestial spheres are not instruments of intelligences but rather [their] organs, as the ear and the eye are the organs of a sensitive power.”

- Proposition 83 safeguarded the doctrine of creation. “That the world, although it was made from nothing, was not newly-made, and although it passed from nonbeing to being, the nonbeing did not precede in duration but only in nature.”

- Proposition 84 condemned the error that the physical world is eternal. “That the world is eternal because that which has a nature by which it is able to exist for the whole future has a nature by which it was able to exist in the whole past.”

- Proposition 85 also guarded against an eternal worldview. “That the world is eternal as regards all the species contained in it, and that time, motion, matter, agent, and receiver are eternal, because the world comes from the infinite power of God and it is impossible that there be something new in the effect without there being something new in the cause.”

- Proposition 86 protected the reality of time and eternity. “That eternity and time have no existence in reality but only in the mind.”

- Proposition 87 guarded the absolute beginning and end of time. “That nothing is eternal from the standpoint of its end that is not eternal from the standpoint of its beginning.”

- Proposition 88 rejected that time is infinite. “That time is infinite at both ends. For even though it is impossible for an infinitude [of things] to have been traversed, some one of which had to be traversed, nevertheless it is not impossible for an infinitude [of things] to have been traversed, none of which had to be traversed.”

- Proposition 89 declared that it is possible to refute arguments of Aristotle if his arguments for an eternal universe contradict revelation. “That it is impossible to refute the arguments of the Philosopher [Aristotle] concerning the eternity of the world unless we say that the will of the first being embraces incompatibles.”

- Proposition 90 carefully noted a distinction between Creator and creation. “That the universe cannot stop, because the first agent has [the ability] to transmute in succession eternally, now into this form, now into that one. And likewise, matter is naturally apt to be transmuted.”

- Proposition 91 asserted the beginning of the universe. “That there has already been an infinite number of revolutions of the heaven, which it is impossible for the created intellect but not for the first cause to comprehend.”

- Proposition 92 condemned the doctrine of the Great Year. “That with all the heavenly bodies coming back to the same point after a period of thirty-six thousand years, the same effects as now exist will reappear.”

Historians still study the writings of contemporaries of this time to ascertain the extent of the drama involved, but these condemnations demonstrate, incontrovertibly and like any other writing produced by Christian scholars, that faith guided the reasoning process. The Condemnations of 1277 are a good reflection of the intellectual climate of the times.

Not Proved by Demonstration

It is noteworthy that St. Thomas Aquinas, who died before the Condemnations of 1277 were issued, also specifically expressed rejection of the eternity of the world contra Aristotle. He credited faith in divine revelation, and not demonstration, for such rejection:

“The articles of faith cannot be proved demonstratively, because faith is of things ‘that appear not’ (Hebrews 11:1). But that God is the Creator of the world: hence that the world began, is an article of faith; for we say, ‘I believe in one God,’ etc. And again, Gregory says (Hom. i in Ezech.), that Moses prophesied of the past, saying, ‘In the beginning God created heaven and earth’: in which words the newness of the world is stated. Therefore the newness of the world is known only by revelation; and therefore it cannot be proved demonstratively.

By faith alone do we hold, and by no demonstration can it be proved, that the world did not always exist, as was said above of the mystery of the Trinity.” [2]

Just as biblical cultures and early Christian writers, the philosophers of the Middle Ages viewed the world as creation, created out of nothing by a merciful, faithful, and loving Creator, with an absolute beginning in time. By rejecting details of the Greek scientific corpus that conflicted with the Christian worldview, the scholars effectively refuted the pantheistic-animistic-cyclical view of the cosmos held not only in Greece, but also in the cultures and religions of Egypt, China, India, and Babylonia. Following that refutation, a realistic physics emerged.

A Realistic Physics Emerged

In the generation after the Condemnations of 1277, Jean Buridan applied this biblical understanding of the cosmos to the common experience of objects in motion. Buridan was not a theologian, but a man with a brilliant scientific mind, confident in his faith to guide his thinking and lay boundaries for reality. He was most interested in explaining natural phenomenon, particularly the motion of objects, and even more particularly, the beginning of all motion. His assent in faith to the tenets of the Christian Creed guided him to assert the most critical breakthrough in the history of science, the idea of inertial motion and impetus. [3] The theory of impetus relates motion to mass of an object, air resistance, and momentum. Buridan specifically refuted the Aristotelian idea that terrestrial motion is due to antiperistasis, impulsion by air moving in behind an object, which was similar to celestial motion. Aristotle believed perfect celestial bodies moved eternally due to a desire to be contact with the divine æther, hence eternal impulsion by divine essence moving in behind an object.

Buridan noted that the Bible does not claim God had to keep his hand on the celestial bodies to maintain their motion. Buridan suggested that the motion of celestial bodies could be answered another way, that God could have created both terrestrial and celestial bodies with physical laws that kept them in motion.

“God, when He created the world, moved each of the celestial bodies as He pleased, and in moving them He impressed in them impetuses which moved them without His having to move them any more except by the method of general influence whereby He concurs as a co-agent in all things which take place; ‘for thus on the seventh day He rested from all work which He had executed by committing to others the actions and the passions in turn.’ And these impetuses which He impressed in the celestial bodies were not decreased nor corrupted afterwards, because there was no inclination of the celestial bodies for other movements. Nor was there resistance which would be corruptive or repressive of that impetus.” [4]

This idea of impetus was the beginning of physics, exact science, where one discovery generates the next at an ever more accelerated rate. Buridan became the rector of the University of Paris in 1327 and taught there until about 1360. In 1377, his theory was formally proposed by Nicole Oresme (1320–1325) and was destined to be adopted by Albert of Saxony (1316–1390), Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543), Galileo Galilei (1564–1642), and Sir Isaac Newton (1642–1727). As has, in fact, occurred since the time of Buridan, physics has grown exponentially with new insights, understandings, capabilities, and realms of observation and measurement at almost unimaginable scales of minuteness and grandeur.

Science and Faith in Conflict?

Some historians have interpreted the condemnations of the University of Paris as antagonistic to the autonomy of philosophy, as a symbol of an “intellectual crisis” in the University and culture of the late thirteenth century and a demonstration of the conflict between faith and what would become science.5 This interpretation is partially correct, but “tension” is a more accurate word than “crisis.” The refusal of the theologians and philosophers to separate the truths of faith from the truths of reason may have caused tension, but hardly a crisis, for this tension to purify Greek thought from whatever conflicted with Christian theology is tension that brought about the intellectual purification that led to the emergence of modern science. The rejection of the ancient ideas of an eternal, cycling, pantheistic, animistic world had to be refuted before a realistic physics, and thus science, could emerge in Christian Europe. This rejection is a distinction that isolates the Christian West culture from all others, a theological distinction that allows one to say, with confidence, that science indeed emerged from a reconciliation of the cosmic view with Christian faith.

There is a lesson for modern-day science in this story. If it seems like, in the century in which we live, science and faith are irreconcilable, the reason is not because they are in actual conflict, but because our knowledge is incomplete. By striving for new understanding toward reconciliation, even amid tension that appears to some as crisis, new insights to realistic breakthroughs can be made. Scientific progress needs the light of faith.

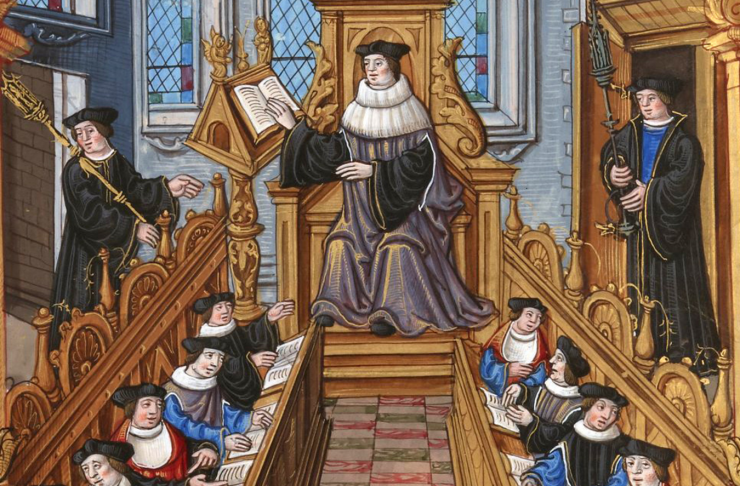

(Image credit: Wikimedia[2])

Notes:

[1] Athur Hyman, James J. Walsh, and Thomas Williams, ed. Philosophy in the Middle Ages: The Christian, Islamic, and Jewish Tradition. Third Edition (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2010), 541-549[3].

[2] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiæ, I, q. 46, a. 2, Sed contra.

[3] Stanley L. Jaki, A Late Awakening and Other Essays (Port Huron, MI: Real View Books, 2004), 50.

[4] Jean Buridan, Book VIII, Question 12[4] of Super octo libros physicorum Aristotelis subtilissimae quaestiones.

[5] Jan A. Aertsen, Kent Emery, Andreas Speer, and Walter de Gruyter. Philosophy and Theology at the University of Paris in the Last Quarter of the Thirteenth Century. Studies and Texts (Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter GmbH& Co., 2000), 3[5].

- [Image]: http://www.integratedcatholiclife.org/wp-content/uploads/Condemnations-of-12771-e1422906243528.png

- Wikimedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Meeting_of_doctors_at_the_university_of_Paris.jpg

- 541-549: http://books.google.ca/books?id=-UN1NaJD0zMC&pg=PA551&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=4#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Book VIII, Question 12: http://faculty.fordham.edu/klima/Blackwell-proofs/MP_C23.pdf

- 3: http://books.google.com/books/about/After_the_Condemnation_of_1277.html?id=JhKwZ6djiDsC

Source URL: https://integratedcatholiclife.org/2015/02/trasancos-condemnations-of-1277/