Gandalf the Prophet — There is More to Life

by Jef Murray | February 11, 2014 12:01 am

[1]

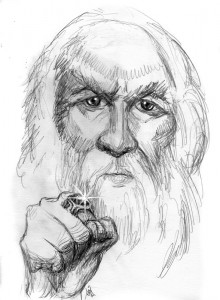

[1]Gandalf the Prophet

Artwork © by Jef Murray

“…there is something greater, much greater, and grander, and happier ‘beyond the veil’, and even perhaps beyond the next turn of the subway train, than anything we can conceive of. There is an enchantment that underlies all of creation, and that exists around the next corner, if only we seek for it.”

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

“Today, I want to talk to you about time. And God wants to talk to you about time; about what you’re doing with your time!” The preacher was standing at the front of the subway car. He had a sheaf of white paper in his hands; as he preached, he passed flyers out to all who would accept them.

I was returning home from the Urbana Theological Seminary. Their conference on Tolkien and the Arts had been bruised, but not broken, by a storm that dumped eight inches of snow on Chicago, and that turned the streets of Champagne and Urbana into treacherous frozen tracts. The attendance was sparse; everyone had been told to stay home unless they must travel. But those who attended were universally interested and interesting.

The papers presented ranged from discussions of leadership qualities, to the nature of teaching, to the ongoing phenomenon of people wanting to “carry on the stories” of Tolkien, to the films (of course), and to the visual arts. But despite the advertised theme of the conference, it occurred to me during the event that all was haunted by a single character from Tolkien’s Legendarium: the wizard, Gandalf the Grey.

In the very first presentation of the morning, Gandalf’s style of leadership was reviewed and expounded upon by Fr. Charles Klamut. Discussions afterwards probed the oft-heard suggestion that Frodo, Gandalf, and Aragorn embodied three of the primary identifications of Christ in the Bible: as Priest, Prophet, and King.

In this pantheon, Gandalf incarnates the role of the Prophet. He is the one who cries out in the wilderness to all who will listen. He is not the hands-on actor or ruler of any realm, but rather he persuades, advises, and takes the role of the far-seeing muse who mulls the myriad threads of time and tribulation. He does not exorcise demons through any power other than his own character and insight, and his “magic” comes from a deeper source than that of Sauron and Saruman, who are, by comparison, tricksters and dabblers.

The second presentation, by Rick Williams, examined Tolkien himself as a teacher; and again, the spectre of Gandalf was raised. Because, when at his best, Tolkien taught by virtue of his own love and enthusiasm, and these qualities were like coals that fired flights of fancy in his young charges. He bolstered courage and creativity, allowing his students to take that flame of intellectual curiosity and fan it into full and satisfying professional careers in many fields.

The third presentation, by Melody Green, looked at the history of J.R.R. Tolkien himself as a fictional character in the works of others. These appear in various media, beginning with books that preceded even the publication of The Hobbit. And it universally appears that Tolkien is depicted in a very Gandalf-like fashion; the fictionalized Tolkien is usually the far-seeing one, the one that first and best understands what is needed or wanted in whatever setting he is cast, and the wise counselor of others.

After lunch, Bryan Mead asked the question whether, in the translation (a better word, to him, than “adaptation”) of Tolkien’s works to film, the filmmakers were true to Tolkien’s own definition of enchantment. That is, since Tolkien himself clearly sought to pull his audience into the world of Faerie along with him (something he was very successful in doing, by any and all counts), was this enchantment he sought to create through his writing maintained successfully on the big screen? Was the “deep magic” of which Gandalf was such an emblem and a herald made manifest?

My own presentation focused on the nature and difficulty of sub-creating visual representations of Middle-earth and other enchanted realms, but also spoke to the vocation of the artist as a calling, akin to a religious calling. Flannery O’Connor tells us that “There is a great deal that has to either be given up or be taken away from you if you are going to succeed” as an artist. A similar statement might be made of anyone who seeks to step into a prophetic role, and it particularly suits Gandalf the Grey, whose very life was given for the sake of his friends and for their quest. It also suits Tolkien himself, who struggled throughout his life to fulfill his duties as a husband, father, and provider while still attempting to find time to create and share his Legendarium.

“God wants you to wake up, people! The hour is late!”

But now, here I am, listening to the subway preacher rail on about the need to arise, to pay attention, to recognize that life is precious and fleeting.

He is right, of course; life is all of these things. But the one thing that is missing from his pronouncements is the one thing never entirely absent from the words and deeds of the Prophet Gandalf. There is no flicker of light behind the eyes, no hint of a smile, no kind words to the weary. There is no veiled glory beneath the tattered clothing, suggesting that the words have their source in something infinitely greater than one might at first suppose. In other words, there is no enchantment; no magic that takes what might be bitter medicine and turns it into the sweet elixir of healing, of light, of love.

For that is Gandalf’s legacy, as it was Tolkien’s; that there is something greater, much greater, and grander, and happier “beyond the veil”, and even perhaps beyond the next turn of the subway train, than anything we can conceive of. There is an enchantment that underlies all of creation, and that exists around the next corner, if only we seek for it.

G.K. Chesterton concludes his book Orthodoxy with the following lines. And although in them he speaks of Christ, his words illuminate perfectly that which we also glimpse in the Prophet Gandalf: that quality that is so sorely lacking in most contemporary prophets, and yet which marks others, such as Tolkien himself, as true Servants of the Secret Fire:

“There was something that He hid from all men when He went up a mountain to pray. There was something that He covered constantly by abrupt silence or impetuous isolation. There was some one thing that was too great for God to show us when He walked upon our earth; and I have sometimes fancied that it was His mirth.”

Jef Murray is an internationally known Tolkien and fantasy artist/illustrator and counterfeit essayist. His paintings, sketches, and writings sprout sporadically from the leaves of Tolkien and Inklings publications (Amon Hen, Mallorn, Beyond Bree, Silver Leaves, Mythprints) and Catholic journals (The St. Austin Review, Gilbert Magazine, The Georgia Bulletin) worldwide. Visit Jef’s website at www.JefMurray.com[2].

Follow Jef on Facebook… Like Jef’s Facebook Page[3].

If you liked this article, please share it with your friends and family using the Share and Recommend buttons below and via email. We value your comments and encourage you to leave your thoughts below. Thank you! – The Editors

- [Image]: http://www.integratedcatholiclife.org/wp-content/uploads/murray-gandalf.jpg

- www.JefMurray.com: http://www.JefMurray.com

- Facebook Page: http://www.facebook.com/integratedcatholiclife#!/pages/Jef-Murray/100554999586

Source URL: https://integratedcatholiclife.org/2014/02/jef-murray-gandalf-the-prophet/