Racism is a preloaded emotion ready to inflict hurt without ever knowing the heart that it lances. It was just such a hatred that motivated two young men to yell from their truck to my husband, “There’s the nigger lover,” referring to our two boys from Kenya. I experienced it in reverse myself many years ago from a group of black women, one of whom flicked her cigarette ashes in my face, simply because I was white. Racism is the most ugly of hatreds, devaluing other human beings and disregarding their very souls.

Racism is a preloaded emotion ready to inflict hurt without ever knowing the heart that it lances. It was just such a hatred that motivated two young men to yell from their truck to my husband, “There’s the nigger lover,” referring to our two boys from Kenya. I experienced it in reverse myself many years ago from a group of black women, one of whom flicked her cigarette ashes in my face, simply because I was white. Racism is the most ugly of hatreds, devaluing other human beings and disregarding their very souls.

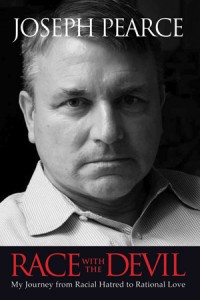

Given my revulsion of racism it was with particular interest that I read Race with the Devil: My Journey from Racial Hatred to Rational Love by world-renown Catholic biographer Joseph Pearce. He was not just a participant but also a recruiter, having led the National Front (a British nationalist white supremacy group). When he was only 15, Pearce launched the youth magazine Bull Dog for the purpose of inciting racial hatred.

Ironically, while reading his book, I discovered that Pearce and I might have crossed paths in London on a Saturday in July of 1977. I was 20, studying political science as part of an exchange program between the University of London and Michigan State University. Pearce was 15 and just for the afternoon, he had joined forces with the Teddy Boys in a street brawl with the Punk Rockers. The Teddy Boys were a retrograde, racist youth cult that dressed out of the Fifties. Punk Rockers represented the new wave. During the ‘70’s and ‘80’s politically charged British youth cults made their music preferences based on political associations.

On this afternoon, my companions and I inquired of one of the shopkeepers as to why the businesses were suddenly locking up mid-afternoon. We learned of the impending brawl. They knew well enough to run for cover before the street violence began. My friends and I pulled out our cameras as the opposing forces gathered. Gangs of young people dressed as if out of American Graffiti prepared for battle against spikey-headed gangs who wore safety pins through their faces. These gangs were a noteworthy tourist attraction to us. We cleared out before the brawl began, but perhaps if I look closely at my old photographs, I will find a young Pearce lending himself out to the fellow hate group.

Later that summer, I made a trip to Dublin by way of Belfast. Two friends and I planned our route to get off at one train station for a walk through Belfast to another station before continuing our journey to Dublin. I wanted to witness what years of fighting between Protestants and Catholics looked like.

It was colorless and bleak. The vibrant Irish green of the Emerald Isle was absent in Belfast; at least the part I saw. One area offered one-stop-shopping through a turn-style entrance where people could be padded down and checked for bombs just once, then be free to shop among many businesses without the constant checks. Our cameras captured a couple gray army tanks that passed by. I wondered what kind of people does this to one another. My grandparents had emigrated from Ireland. I grew up proud to be Irish and was even named after St. Patrick, the country’s patron saint. But being Irish was not enough in Northern Ireland; one had to choose sides.

Pearce writes of his frequent trips to Northern Ireland, eager to share in the hatred against Catholics—or in his father’s words: bead rattlers. “The anti-Catholicism that I learned at my father’s knee was deepened and darkened by my involvement with the Protestant Loyalists of Northern Ireland,” he writes. “I had travelled to Ulster on many occasions over the previous few years at the very height of the Troubles which would claim almost four thousands lives before the Good Friday peace agreement was signed in 1998.” Pearce had joined the anti-Catholic Orange Order, a secret society that fraternized with several terrorist organizations. During that time, he witnessed both Irish comrades and opponents die in attacks.

Pearce was an avid reader and intellectual although hate was woven into most of his literature. He did not just read, however, he also contemplated. Through such ruminations, Pearce began to break from neo-Nazi philosophies, but remained blind to the evil of white supremacy for a while longer. For that, he paid a steep price. On January 12, 1982, he was convicted under Britain’s Race Relations Act, for publishing material likely to incite racial hatred. The government’s goal of muting Pearce’s message with his 6-month prison sentence was undermined when his followers hailed him as a hero for the cause. But in 1985, when he was arrested again for the same charge and sentenced to 12 months in prison, much of the fire had gone out of him.

“The first couple days of the second prison sentence were perhaps the darkest of my life,” Pearce writes. “Broken in spirit and troubled in mind, I was painfully aware that I was not the brave and brazen political soldier who had gone to prison four years earlier.”

During the interim, Pearce had encountered love through random Christian acts including one from a political enemy and another from a police officer. But, the silver bullet to dissolving his hatred was the discovery of author G.K. Chesterton. By way of wit and wisdom, Chesterton delivered love and truth the likes of which Pearce had never experienced. Pearce later read other Catholic writers and through his literary friends, he was introduced to Jesus Christ and the Catholic Church.

“Amidst the ruins of my old life, the seeds of a new life were germinating,” he writes. “Imperceptible, my faith in race and nation was being sapped by my embryonic faith in Christ and His Church, a faith which was in gestation, not fully formed but continuing to grow, deep inside, with every passing day.”

Upon his arrival at Wormwood Scrubs Prison to begin his second sentence, Pearce surprised even himself during the customary intake questions. When asked what his religion was, he replied “Catholic.” But it wasn’t. “Yet, I was more of a Catholic than anything else,” he writes. Not until that moment did he truly realize that he had incrementally embraced the truth of Catholicism. It was a baptism of desire that had to suffice until after his release when he could enter the Church officially.

Pearce left his old politics behind. “The pagan and the Christian could not coexist,” he determined. Pearce became a true “bead rattler,” falling in love with Mary as his Queen, and with Christ as his King.

It was great thinkers that led Pearce to Christ through more than just reason. “I now understand that love, as well as reason, was necessary for my conversion, but I understand also that the love to which I am indebted is as rational as the reason.” For Pearce, his healing led to places he never could have imagined—to the United States, to a happy Catholic marriage and family, and to the publication of almost twenty books, including biographies of G. K. Chesterton, C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Alexander Solzhenitsyn. Today, he is also an accomplished teacher and speaker, and Writer-in-Residence at Thomas More College.

Pearce offers proof that God’s love can access even the seemingly unreachable heart. It is a love that our baptism commissions us to share; to be that example of love that can penetrate the most hardened of hearts. After all, Joseph Pearce was once an angry, hate-filled hooligan. There are plenty more where he came from, waiting to be loved into the heart of Jesus Christ through our prayers and examples.

Patti Maguire Armstrong and her husband have ten children. She is an award-winning author and was managing editor and co-author of Ascension Press’s Amazing Grace Series. She has appeared on TV and radio stations across the country. Her latest books, Big Hearted: Inspiring Stories from Everyday Families and children’s book, Dear God, I Don’t Get It are both available now.

To read more, visit Patti’s Catholic News and Inspiration site. Follow her on Facebook at Big Hearted Families and Dear God Books.

Looking for a Catholic Speaker? Check out Patti’s speaker page and the rest of the ICL Speaker’s Bureau.

If you liked this article, please share it with your friends and family using the Share and Recommend buttons below and via email. We value your comments and encourage you to leave your thoughts below. Thank you! – The Editors