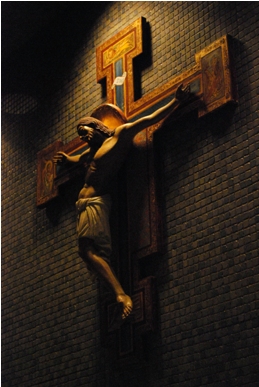

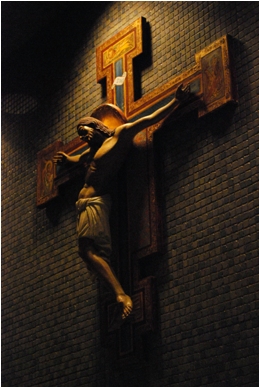

Photography © by Andy Coan

Holy Week is a week where we are reminded of the inextricable link between humility and suffering. Christ’s passion radically embodies the surrendering of self-will to God’s-will, the hurt of unjust humiliation and the willingness to embrace the suffering of the cross.

Suffering Towards and Not Away From Christ

Every person experiences suffering during this life. There is no getting around it. The question is when suffering comes our way, will we see it as an opportunity to outwardly turn toward Christ or as a curse that turns us inwardly and away from Christ? Our response to this question has a profound impact on the way we choose to live life and on the salvation of our soul.

Consider that Christ was not crucified alone. Rather, he was crucified with two serious sinners who were criminals, one on his right and the other on his left. All three, as men, suffered the same painful death of crucifixion. Still, the criminals responded in a different way to their own suffering and to the significance of Christ’s sacrifice.

One criminal saw only his own suffering and was unrepentant. He blindly missed Christ’s redemptive act by turning away in a mocking manner and smugly chided, “Are you not the Messiah? Save yourself and us.”

The other criminal, who was suffering the same fate at the same moment, saw matters dramatically differently. He turned toward Christ in a contrite way. Instead of inward pride, this criminal demonstrated outward humility by fearing God, by recognizing that unlike Jesus, he and his counterpart had been justly condemned for their criminal conduct, and by demonstrating an overt desire to be in relationship with Jesus when he entered into his kingdom.

In Mel Gibson’s Passion of the Christ, the unrepentant criminal has his eyes pecked out by a raven, artistically signifying the blindness of this man’s pride that eternally separates him from Christ. On the other hand, our church tells us that the contrite criminal achieves eternal life and becomes the patron saint (Saint Dismas) of those condemned to death, exemplifying that it is never too late to turn toward a merciful God, no matter how scarlet one’s sins may be.

The Mask of False Humility

Much of what is proffered as “humility” is likely false humility. You know, the kind of convenient, voluntary, “awe shucks,” comments made when the praise we secretly seek actually comes our way. Oftentimes, the mask of false humility consists of publicly deprecating oneself, one’s god-given gifts and talents, and one’s providential accomplishments for the sake of receiving approval from others

Yet, behind the mask of false humility is the notion of self and one’s own importance. Instead of seeing one’s insignificance in relationship with God, false humility strives to convince ourselves and others that our will is likely God’s will.

False humility thinks it has achieved a sense of humbleness in comparison with others. Even so, a truly humble person does not refer to themselves as humble, because they are not thinking of themselves at all. Rather, they are intent on submitting to God’s will and focusing on how they can love others.

True Humility Embraces the Suffering of Cross

Humility, true humility, recognizes the nothingness of self in relation to God and gratefully accepts the providential humiliations that come our way. With eyes fixated on Christ and not on self, authentic humility embraces the sufferings at hand, believing that God is molding us for eternity and perhaps using us in a way that we currently cannot see to divinely touch others.

Still, true humility that is divorced from self is rare. It is the kind of humility that shirks itself from pride so that we might know God and his divine providence as they are, not as we may wish them to be. It is the kind of humility that C.S. Lewis speaks of in Mere Christianity when he says, “He (God) is trying to make you humble in order to make this moment possible: trying to take off a lot of silly, ugly, fancy-dress in which we have all got ourselves up and are strutting about like the little idiots we are. I wish I had got a bit further with humility myself: if I had, I could probably tell you more about the relief, the comfort, of taking the fancy-dress off—getting rid of the false self, with all its ‘Look at me’ and ‘Aren’t I a good boy?’ and all its posing and posturing. To get even near it, even for a moment, is like a drink of cold water to a man in a desert.”

Humility is not self-donned but apt to be achieved involuntarily through suffering and experiencing humiliation itself. It is oftentimes garnered through the trials and fires that life unexpectedly imposes, where the impotent self sooner or later surrenders to the omnipotent Creator of us all. Learning to grow in a humility born from Christ’s sacrificial love is learning to be grateful to God, not for what is graciously given, but also for what is painfully taken at times.

Holy week is all about humility and why our suffering seen through Christ’s passion is the surest path of getting there. And in the final analysis, Holy Week offers a heavenly roadmap for humility that recalls, “Blessed are ye when they shall revile you, and persecute you and speak all that is evil against you, untruly, for my sake: Be glad and rejoice, for your reward is very great in heaven” (Matthew 5:11-12).

Please help us in our mission to assist readers to integrate their Catholic faith, family and work. Tell your family and friends about this article using both the Share and the Recommend buttons below and via email. We value your comments and encourage you to leave your thoughts below. Thank you! – The Editors