A San Francisco based company known as Neocutis, now offers a skin cream that is made from human fetal tissue. It claims that this product can “turn back time to create flawless baby-skin again”.

A San Francisco based company known as Neocutis, now offers a skin cream that is made from human fetal tissue. It claims that this product can “turn back time to create flawless baby-skin again”.

If potential customers are a little squeamish about taking advantage of abortion to improve their complexion, the Neocutis website reassures them that theirs is a “limited, prudent and responsible use of donated fetal skin tissue,” and one “that is respectful of the dignity of human life”.

Neocutis is aware that some interest groups have raised objections about how it develops its products. But this manufacturer is broad-minded and respects a diversity of opinion: “We respect differing views on medical research practices”. Reading between the lines, one concludes: since we are broad-minded enough to respect your values, you should be broad-minded enough to respect ours. But are all values equally respectable? And is a value acceptable simply because it falls within the purview of broadmindedness? Would it be narrow to disrespect approaches that are “unlimited, imprudent, and irresponsible”?

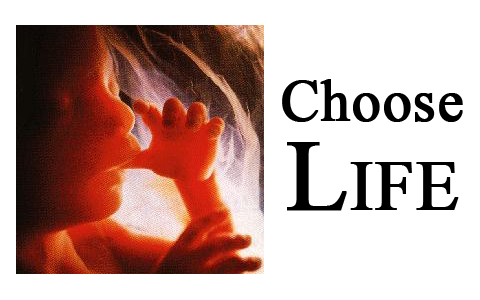

Neocutis’s tactfully chosen words, however, do not conceal a moral discrepancy. On the one hand, the medical profession can be casual about aborting unborn babies and then, on the other hand, be so positive about developing a skin cream from their tissue that can restore people’s complexion to a “flawless baby-skin” texture. There is something jarring about having such little regard for unborn human life and such a high regard for its tissue. Actually, Neocutis is positively rhapsodic about its skin cream: “Inspired by fetal skin’s unique properties, Neocutis’s proprietary technology uses fetal skin cells to obtain an optimal, naturally balanced mixture of skin nutrients”.

Lisa Klassen, a Grade 11 student, came to her high school one day in St. Thomas, Ontario, wearing a pro-life shirt that read, “Abortion is Mean”. Her principal sent her home and suspended her on the grounds that her message was “offensive”. Her school’s newspaper, ironically called The Titanium, was not allowed to print her defense.

Now, a student whose complexion has been restored, thanks to Neocutis, to a “flawless baby-skin” texture can come to school without fear of being suspended. Her implied message, perhaps known only to her, is that “abortion is good”. And as long as no one knows how she got her radiant countenance, no one will be offended. The whole point of education, so it appears, is to keep students in the dark.

The notion that the individual is supreme and can exploit others for his own benefit has become well-established in present-day society. Consider, for example, the vampire subculture that is aided and abetted by TV series, movies, novels, games, apparel, websites, and a litany of consumer products. Regaining youth and achieving immortality at the expense of another person’s blood has a strong appeal for many, especially the younger set.

Sarah Khokan manages a Toronto boutique that sells vampire clothing, makeup and jewelry, mostly to customers in their teens and 20s. She views would-be vampires as being attracted to “the ideal of living forever and being immortal”. The end is good, but are vampire wannabes concerned about evaluating the means? And even though the vampire subculture is largely an imaginative game, its moral deficiencies should not be ignored.

The “Temple of the Vampire,” that advertises itself as a religion, promotes the supremacy of the individual. Its website promises great and lasting benefits to all its followers: “We want you to uplift your life and transcend your death. And you can do so by embracing a powerful mythological symbol of immortality as your own: The Vampire”.

Causing the death of another in order to obtain benefits for oneself, of course, is macabre. But it also contains a logical contradiction. If each individual believes in his own supremacy, what results is not a society of super-achieving, super-satisfied individuals, but a society of predators in which everyone is at the mercy of everyone else. It is the nightmare world that 17th Century philosopher Thomas Hobbes envisioned when he wrote about bellum omnium contra omnes (the war of all against all).

Vampirism and Christianity are poles apart. They differ as do darkness and light. Vampirism believes that there is only so much blood and individuals must take it from others in order to keep on living. Christianity believes that there is no limit to love and that each person should freely give love to his neighbors. Vampirism produces an anarchy of predators. Christianity produces a community of persons. It should not be difficult to decide in which realm one should want to reside.

Enhancing one’s complexion by using skin-cream derived from an aborted human fetus is not unrelated to the essential dynamic of vampirism. They both represent an excessive concern for eternal youth and a willingness to exploit others in order to achieve that end.

Audrey Hepburn, one of Hollywood’s most glamorous actresses, read one of her favorite poems to her children on the last Christmas she spent on earth. The poem, though actually composed by Sam Levenson, came to be known as “Audrey Hepburn’s Beauty Tips”. The first and last stanzas are particularly instructive: “For attractive lips, speak words of kindness. . . . The beauty of a woman is not in a facial mode, but true beauty in a woman is reflected in her soul. It is the caring she lovingly gives, the passion that she shows, and the beauty of a woman with passing years only grows.”