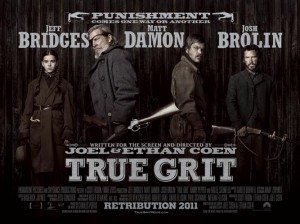

“True Grit,” the 1969 film starring John Wayne, was the first “grown-up” movie I saw as a kid. I was nine years old at the time, and I remember the experience vividly. I also discovered, through that film, that I had a gift for mimicry. For years afterward, at family parties, I was invited to reproduce the Duke’s distinctive drawl: “I wouldn’t a-asked you to bury him if he wann’t dead.” The Coen brothers, the auteurs behind “Fargo,” “No Country For Old Men,” and “A Serious Man” are among the best and most spiritually alert filmmakers on the scene today. And so it was with great excitement that I learned that the Coens had produced a re-make of “True Grit.” Though their version is far different from the original, I found it compelling, especially in the measure that it brings the religious dimension of the story to the fore.

“True Grit,” the 1969 film starring John Wayne, was the first “grown-up” movie I saw as a kid. I was nine years old at the time, and I remember the experience vividly. I also discovered, through that film, that I had a gift for mimicry. For years afterward, at family parties, I was invited to reproduce the Duke’s distinctive drawl: “I wouldn’t a-asked you to bury him if he wann’t dead.” The Coen brothers, the auteurs behind “Fargo,” “No Country For Old Men,” and “A Serious Man” are among the best and most spiritually alert filmmakers on the scene today. And so it was with great excitement that I learned that the Coens had produced a re-make of “True Grit.” Though their version is far different from the original, I found it compelling, especially in the measure that it brings the religious dimension of the story to the fore.

The leitmotif is set in the opening moments of the movie, as we hear Mattie, the narrator and principal character, say in voice-over “the only thing in life that’s free is the grace of God.” The film will unfold as an extended meditation on the play between justice and mercy, between what is owed and what is given as a grace. Fourteen year old Mattie, whose father had been killed in cold blood by a man he had befriended, lives in a world of strict justice, of give and take, of contracts and obligations. Bound and determined to see her father’s killer hanged, Mattie hires a wizened old law man named Rooster Cogburn (played with characteristic naturalness by Jeff Bridges) and gives him the charge of tracking down the murderer. We get a delicious taste of Mattie’s personality as she, with lawyerly skill and fierce persistence, wrests from an oily horse-trader the money she needs to pay Rooster. And when Cogburn leaves without her, convinced that the teen-aged city slicker would only slow him down, she rides her horse right across a raging river to catch up to him—and then reminds him that he is in breach of contract! Mattie is a mulier fortis, a woman not to be trifled with.

She moves with Rooster and Le Boeuf—a Texas ranger who is also looking for the murderer—into Indian country, a place of lawlessness, where drifters live outside the constraints of polite society. They corner a couple of members of Ned Pepper’s gang, for Rooster is convinced that the killer might have joined forces with these desperados. After a shoot-out and a violent interrogation, two men are dead and a third is wounded. The next day, by the bank of a river, Mattie encounters her father’s killer and manages to wound him before being captured by Ned Pepper and his men. In the most stirring scene in the film, Rooster manages, single-handedly to take on the entire Pepper gang, holding the reins of his horse in his teeth and firing with both hands. After this encounter, four more men lie dead. Finally, Mattie frees herself and shoots to death her father’s murderer, but the recoil on the gun is so strong that she is pushed into a snake pit, where she receives a bite on the hand. I’ll get back to the snake pit in a moment, but notice first what this canny fourteen year old girl’s lust for vengeance has wrought: eight dead men. She wanted only to bring her father’s killer to justice, but the single-mindedness of her pursuit conduced toward a disproportionate, even barbaric, result, something far beyond the requirements of justice. Her excessive and one-sided passion for righteousness kicked her into a den of snakes, and no one with a Biblical sensibility could miss the symbolic overtone of this kind of fall.

As she lies helpless and desperately injured, Mattie looks up and sees Rooster Cogburn lowering himself by rope to the bottom of the pit. He cuts into her wound and sucks out as much of the poison as he can and then he brings her back up, places her on a horse and commences a furious ride to the nearest doctor who is many miles away. When the horse gives way from sheer exhaustion beneath him, Rooster picks up Mattie in his arms and carries her through the night to the doctor’s home. Now Cogburn is a man of the law, and like Mattie, he was aiming to bring a killer to justice, but what these heroic actions on behalf of the girl reveal is that he more than that. His passion for justice is accompanied by, even surpassed, by his mercy, his graciousness, his willingness to give even when that giving was not, strictly speaking, owed.

As the film comes to a close, we have fast-forwarded many years into the future, and a still prim, unmarried, and somewhat cold Mattie has just learned of the death of Rooster Cogburn. We then see that she has but one arm. Though Rooster’s graciousness saved Mattie’s life, the doctor, evidently, was not able to save her limb. And as the final credits roll, we hear the beautiful old spiritual “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms,” which speaks of the “fellowship and joy divine” which comes from “leaning on the everlasting arms” of God. Rooster had carried Mattie in his two arms, evocative of both justice and mercy, attributes that come together supremely in God. Mattie’s tragedy is that she had only justice, only one arm. The same Coen brothers who gave us a powerful image of God in the tornado at the conclusion of “A Serious Man” and in the pregnant police officer in “Fargo” have given us still another in the strong arms of Rooster Cogburn.