There’s a common phenomenon that occurs when a movie is made based on a best-selling book. Those who have never read the book go to the movie and often appreciate the story on its own merits, even if, as happens frequently, many of the elements that gave life to the original work were not included or changed outright. Those who have read the work, however, while they may still appreciate the film as a coherent whole, often acutely feel the absence of those eliminated or emendated elements, which, even though non-essential, are part of the story. They’re often left commenting how the film could have been improved had those original elements been more faithfully rendered.

There’s a common phenomenon that occurs when a movie is made based on a best-selling book. Those who have never read the book go to the movie and often appreciate the story on its own merits, even if, as happens frequently, many of the elements that gave life to the original work were not included or changed outright. Those who have read the work, however, while they may still appreciate the film as a coherent whole, often acutely feel the absence of those eliminated or emendated elements, which, even though non-essential, are part of the story. They’re often left commenting how the film could have been improved had those original elements been more faithfully rendered.

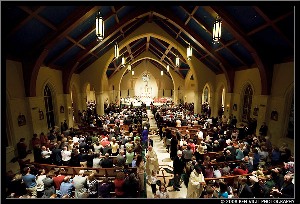

That cinematic experience has long been the liturgical experience of Roman Catholics with the new order of the Mass that followed the Second Vatican Council. Those with or without exposure to the text of the Latin original can and do appreciate and love the Mass for what the Mass is and can certainly derive enormous spiritual nourishment from the structure of the rite and the English translations of the order of Mass and the variable prayers. Those, however, who are familiar with the Latin typical edition have been in many places disappointed that the Scriptural, patristic and poetic richness of the original has not been adequately translated. That is, until now.

On Friday, August 20, Cardinal Francis George, the President of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, announced that the Vatican had given final approval for the new English translation of the Roman Missal. The changes will go into effect in U.S. parishes on November 27, 2011, which will be the first Sunday of Advent and the beginning of a new liturgical year. The delay of fifteen months is to give liturgical publishing companies plenty of time to prepare beautiful and sturdy new missals and to provide, musicians and composers, priests and faithful the opportunity to accustom themselves to the new translations, understand the reason behind the changes within the context of a profound liturgical catechesis, and experience their implementation as a smooth rather than an abrupt occurrence. At The Anchor, we will be inaugurating a series specifically on the changes, another on the history of the liturgical movement and a third on liturgical questions-and-answers, to help our readers learn what changes are on the way and why, within the large context of the Church’s theology and practice of the liturgy.

With the new translations, the structure of the Mass will remain the same and the vast majority of the words prayed by the faithful will either remain identical or have only slight variations. The biggest changes will occur in the prayers said by the priest, which have been thoroughly retranslated in order to help them correspond more faithfully to the Latin original and the ancient texts on which the Latin is based.

When the Roman Missal was translated into English for the first time in the early 1970s, translators worked under a principle of “dynamic equivalence,” in which they sought adequately to render the meaning of the Latin words in terms and phrases immediately accessible to English Mass-goers. They broke up lengthy sentences into short ones. They reduced the vocabulary of the Latin original, using the same English word to express various Latin originals. They eliminated intensifying expressions, such as the use of multiple adjectives to modify the same noun. They produced a very intelligible, direct and at times colloquial text that has served us fairly well over the span of four decades.

But there were a few important things that were lost in translation and needed to be remedied.

First, there was a loss of a certain sacred vocabulary and sentence structure distinguishing the way we address God from the way we address others. It is important in the Church’s liturgical prayer — especially in an age when there is a dramatic loss of the sense of the sacred — that the language of our vocal prayers reflect the reverential awe we need to have in approaching God’s divine majesty as beloved children.

Second, there was a loss of “catholicity” or “universality” when the principle of “dynamic equivalence” was used by various language groups, which led to noticeable variations in the prayerful experience of Mass for those attending Mass in different tongues. For example, at the beginning of the Mass when the priest first greets the people, in English the people have responded “and also with you,” in Spanish, “and with thy spirit,” and in Portuguese, “blessed be God who has reunited us in the love of Christ.” During the penitential rite, English and French speakers have said, “through my own fault” striking their breast once; Portuguese speakers have twice said the expression and twice stricken their breast; Spanish and Italian speakers have done both three times. At the end of the offertory, when English speaking priests have said, “Pray, brothers and sisters, that our sacrifice may be acceptable to God, the Almighty Father” and the faithful have responded, “May the Lord accept the sacrifice at your hands, for the praise and glory of his name, for our good and the good of all his Church.” French priests have instead stated, “Let us pray together as we offer the sacrifice of the whole Church” and French faithful have responded “for the glory of God and the salvation of the world.” In German, the most popular option for this important dialogue has been for the priest and people to skip it all together, with the priest’s simply saying “Let us pray” and the people responding nothing.

These changes, both individually and collectively, are not minor or inconsequential. Because the vernacular translations vary so much —veering from the Latin standard in assorted ways and to different degrees — the experience of the Mass in the various languages varies well beyond the change in idiom. This was never intended and is one of the items that the Church was seeking to remedy in these revisions, done under a principle of “formal equivalence” that seeks to have all translations adhere much more tightly to the original. To the extent possible, the only thing that varies from one vernacular translation to another is the given word in a language, not the thought and not the liturgical structure. This is crucial because the Church believes as she prays — the ancient principle of lex orandi, lex credendi — and when there’s substantial variance in the way the Church prays the Mass, there will be consequences in the faith across language groups.

Third, the new translations are also trying to rectify another lost element: the readily-discernible link between liturgical language and Sacred Scripture. In the Latin Missal, many of the Mass texts are taken verbatim from the inspired words of the Bible, which provide the full context for them. Many of these biblical-liturgical links were missed in the original vernacular renderings. One example of this, in English, happens with the prayer, “Lord, I am not worthy to receive you.” The new translation will conclude, “…under my roof, but only say the word and my soul shall be healed.” This literal translation from the Latin is taken directly from the humble prayer of the Centurion when he asked Jesus to heal his servant (Mt 8:8). In praying these words, we are explicitly calling to mind that we are addressing the same omnipotent and merciful Jesus he addressed. The more the liturgy prays explicitly with the inspired words of the Bible, the easier it will be for priests and faithful to ground their lives in that saving revelation and to speak it.

The new translation of the Roman Missal responds adequately to these issues and is a substantial improvement over what we are presently using. It took eight years to accomplish, but those eight years were well-spent. It should result in a more beautiful, more sacred and more catholic experience of the Mass.